The blog I attended was called Black and Born Outside of the U.S., which included several USD speakers from Africa and the challenges and obstacles they faced when they first arrived in the U.S. The discussion contained many questions on how those students/teachers adapted to the social and political changes from Africa to the U.S. Some questions that were involved in the discussion were the cultural shocks, unexpected challenges before arriving, perception of racial identity in Africa versus the U.S., and in what ways the audience could support those that identify as Black who were born outside of the U.S. These themes and narratives of this program help understand how different the history and discrimination of African and African Americans went through, this is due to the country of origin, socioeconomic background, and personal circumstances and the different experiences that they both faced.

One of the most significant issues African students/teachers faced was not being entirely accepted into the African American community, and moving to a different country, especially when cultural and social differences are very intimidating. Language was one of the issues that the African students faced because the vocabulary and use of words were much different between the African and African American communities. Even being the same skin color, there was a sense of isolation and physical differences between the African and African American. They were still seen as outsiders. According to author Ohimai Amaize, he says “For a very long time in the twentieth century, during Jim Crow years in particular, African-Americans were encouraged to shun the idea of a connection to Africa, to think poorly of Africa–to celebrate traits in themselves, which supposedly distanced themselves from Africa, in other words, to think of themselves as more cultured, more Christian, more White, more civilized than Africans and therefore to look at ‘Africanness’ as a matter of shame or a kind of taint that need to be avoided” (Amaize, 2021). This quote represents the harsh reality of how African Americans were sought to view Africans. However, they had little knowledge of how to judge Africans.

In Africa, the students/teachers were more exploited by tribalism than racism. The perception of race was more common than ethnicity in America; when growing up in Africa, race was not something to consider. For example, living in Kenya was more about what tribe you came from rather than the color of your skin; however, African and African Americans, to some degree, had the same sense of tribalism, knowing what is most important and what to value in life. The black identity had to do a lot with the location you grew up in. Africans at first did not understand the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Africans had an uneducated belief that African Americans had much more resources and overall quality of life than Africans. African people had to undergo real-life problems such as tribal wars, food, water, shelter, etc. But when African people came to the United States, they understood the horrific history of racism and segregation that African Americans went through. They understood how discrimination affected every aspect of life, employment, education, and interactions with law enforcement. During the discussion, one of the African students included, “You’re the ones who sold us” meaning African Americans have that perception and assumption that African people were a big reason for bringing enslaved people to the United States. This created a boundary between African and African Americans because they didn’t believe that Africans had the same experiences toward slavery as much as African Americans did. These cultural differences and experiences between African and African Americans lead to misunderstanding and hesitation rather than embracing and understanding their differences and connecting from similar backgrounds.

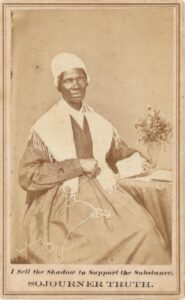

Although there are many differences regarding historical background and ethnicity, Africans and Americans are more similar than different. African immigrants often experience discrimination in the United States. “Indeed, black Africans are at greater risk for indicators of discrimination such as skill devaluation, underemployment, and lower earnings despite high levels of human capital among this group” (Saasa p.198). An apparent similarity between African and African Americans is that they both have African heritage. While the experiences of slavery were different for African and African Americans, they both contain ancestral roots from Africa. African culture played a significant role in the influence of African American culture. From the beginning of slavery in the United States, African culture was crucial to slavery’s way of life. Dancing such as Ring Shout “Practiced in both the West Indies and North America, the ring shout combined West African – based music and dance traditions with the passionate Protestantism of the Second Great Awakening to create a powerful new ritual that offered emotional and physical release” (Freedom On My Mind p. 222). This quote explains the significant importance of cultural dancing and music because enslaved people could only find a few joys in the world. The Ring Shout was a substantial element in their culture. Another similarity between African and African Americans was family and community.

What Africans and African Americans care for and value most is their families. During the Black Power movement, all African Americans had was their community, it was them against the rest of the country. Staying close to family was vital for self-growth; families taught the values of preserving cultural traditions and the sense of core values of how to be a good person/citizen. These essential life lessons are necessary for people to make good choices and stay on the right path. One of the essential values of families and communities was the sense of belonging and the safeness and comfort of that feeling. Being a minority in a country is isolating and intimidating, but having a strong community/family can help overcome those fears and result in a more positive and happier life. It is imperative to understand that African Americans may have social and cultural differences in today’s world. Still, they will always have similarities no matter what, and to embrace the similarities, both African Americans and Africans need to understand the history of each other. By doing that, there will be a clearer mind on both sides.

Although there are many differences between Africans and Americans, which may prevent the connection between the two, there are also many similarities. Coming from Africa to America is challenging because people of the same skin color see you as different and therefore don’t fully accept you. While that may seem complicated, undertaking their reasons for that and adapting to it is the only thing that can be done. Both African and African Americans need to understand that they are the minority race of the United States, and they should not divide themselves. Instead, they should embrace their cultural and social differences and come together. At the same time, their language and culture may be different today; in the past, dancing and music such as Ring Shout was part of the foundation of that culture. Family and community are vital elements in African and African American cultures; they need a solid community to self-grow and adapt to the cruelty and discrimination of the outside world. This issue with African and African American citizens in the United States is improving; dividing them is never the answer because isn’t that what they are trying to fight? It is crucial to understand the Black history for this situation because then both African and African Americans will have a much better understanding of each other, leading to embracement rather than separation.

Works Cited:

Sassa, K Saasa. “Discrimination, Coping and Social Exclusion Among African Immigrants in the United States: A Modern Analysis” Google Scholar, Oxford Academic Social Work 12 June, 2019 p. 198

https://academic.oup.com/sw/article/64/3/198/5514032

Ohimai, Amaize. “The Social Distance between Africa and African-Americans” JSTOR DAILY

14 July, 2021.

https://daily.jstor.org/the-social-distance-between-africa-and-african-americans/

White Deborah Gray, Bay Mia, Martin Jr. E Waldo. “Freedom On My Mind” New York City, Bedford/ St. Martins, 2021

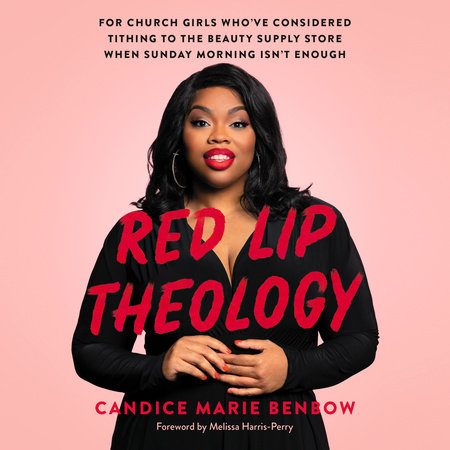

Red Lip Theology is a call to action for Black women to use their voices and take up space in their religion and culture. The name “Red Lip Theology” Is inspired by the symbol of red lipstick, which represents both femininity and boldness. “Men dominated church leadership, but women constituted most of the members and regular attendees and did most of what was called church work. Women gave and raised money, taught Sunday school, ran women’s auxiliaries, welcomed visitors, and led social welfare programs for the needy, sick, and elderly. They were also prominent in domestic and foreign missionary activities. One grateful minister consistently offered “great praise” to the church sisters for all their hard work” (White, Bay & Martin, 2021). Benbow asks herself the question,“What is owed to black women for that level of religiosity, what is owed to black women for that level of commitment?” where she answers, “Red Lip Theology was and is my way of trying to make sense of that.”

Red Lip Theology is a call to action for Black women to use their voices and take up space in their religion and culture. The name “Red Lip Theology” Is inspired by the symbol of red lipstick, which represents both femininity and boldness. “Men dominated church leadership, but women constituted most of the members and regular attendees and did most of what was called church work. Women gave and raised money, taught Sunday school, ran women’s auxiliaries, welcomed visitors, and led social welfare programs for the needy, sick, and elderly. They were also prominent in domestic and foreign missionary activities. One grateful minister consistently offered “great praise” to the church sisters for all their hard work” (White, Bay & Martin, 2021). Benbow asks herself the question,“What is owed to black women for that level of religiosity, what is owed to black women for that level of commitment?” where she answers, “Red Lip Theology was and is my way of trying to make sense of that.”