James Scott

Professor Miller

History 128

12 May 2023

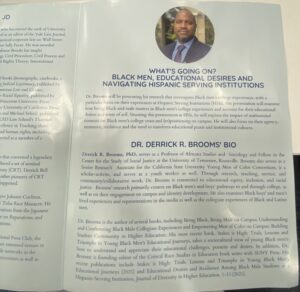

Black History as USD

African American history is a history of people, places, and things. Taking the class of African American history is a stepping stone to realizing and understanding the day-to-day life and life and the history of an African American cannot fully be comprehended without experiencing it personally. Although the black experience cannot ever be summarized, in Roy L. Brooks’ distinguished lecture series Dr. Derrick Brooms touches base on topics such as the aspects of African American history he experienced in his life. He explained how black people and based on his personal experience black men and boys have a box they are put into on where they should be, what they should be and how they should be it, without the opportunity to start with a clean slate. He touches on topics such as youth as a black boy, the black college experience, and being subject to racial stereotypes ultimately showing why the theme of this subject is significant to the understanding of African American history.

The first topic Dr. Brooks touched on was the College experience as a black man or as he called it “the black college experience”. As a young man, he grew up in the south side of Chicago in a racially segregated neighborhood and was supposed to end up in many places, but college was not one of those places. He took pride in being able to be relatable, in his presentation he said “Many young black children hear stories of success from the mouths of those who were born into it”, he is not one of those people. Just like many other black youth, Dr. Brooks grew up playing sports what he emphasized was that he played football and ran track, with that being said he wasn’t a football player nor was he a track runner he was Derick Brooks saying “Sports are what I, not who I was”. This is one of many boxes that the black male population is put into by society, as the image of a well-paid black professional comes with the assumption that their success was obtained by running a ball or performing on a stage. Despite his knowledge of self when he stepped foot on a college campus the question, he received from his white counterparts were of the origin such as what sport do you play and was instantly put into a category or a box. If he was not judged based on the assumption that he had to be an athlete he was judged about where he was from. He then used this to go into another point of the black college experience, he honed in on the comparison of black students and their white counterparts when it came to success in education. For example, according to College Dropout Rates 2023, 52% of black students drop out of a 4-year institution per year while only 42% of white students drop out of the 4-year institutions they attend. When this information is presented what isn’t presented is that of those 52% of black students 65% of those African American students are independent meaning, they are trying to maintain a full-time job and family responsibilities while pursuing a degree. Due to situations like these are the root of Dr. Brooms’ hypothesis that black educational success cannot be based on a comparison between black and white students. The reason for this is the uniqueness of the black educational journey as he called it. He faced problems as a black man his white comparable did not for example, people were more worried about how he dressed, how his hair looked and how he talked than they were with is intellectual ability.

The next key topic Dr. Brooks touched upon was the perception of black people. With confidence, he said, “I am at this point in my life because of the people before me, I’m here because I stand on their shoulders of them”. This very quote is significant when acknowledging how African Americans are perceived in America because the negative assumptions, views, and stereotypes date back to earlier than the 1930s. During this time black people were presented to the public eye through entertainment that painted them in a negative light. One example of this according to Freedom on My Mind is from the 1930s where Stepin Fetchit was the most popular black actor on page 741 the text says “The most popular black actor of the 1930s was Stepin Fetchit (Lincoln Perry), known as “the Laziest Man in the World.” Playing the slow-talking, dim-witted, shiftless sidekick to white costars”. This character showed black people as uneducated and inferior to white Americans thus creating a negative stereotype that would spiral for generations to come. Preconceived notions about African Americans come with assumptions backed up by no factual evidence. Dr. Brooks says assumptions get made off of circumstances such as you live in the hood then a hood rat is all you’ll ever be. His personal experience with this subject is how when he lived in a single-parent black household and was labeled as “at risk”, no one asked him about his life or they would’ve known his father lived down the street and his grandmother lived in the home with him and his mother. As he might’ve lived in what was labeled a single-parent household he was also subject to a multi-generational household.

The learning of African American history at the University of San Diego and the program presented by Dr. Brooks come full circle to make a deep connection. That connection is that the black experience is one that is different from any other. On one side you have the educational part of history being taught, explaining how America was built off the back of the enslaved and the progression black people made despite the obstacles and barriers that were placed on their road to success. Dr. Brook’s program for the most part dives into the explanation of the black experience through a general sense based on similar personal experiences felt by African Americans across the country. In class the material begins with where black people first come from, then how a system was built to decelerate their progression, and next what they did to get over those systems set in place. In comparison Dr. Brooks does the same, speaking about his upbringing as a black kid from a segregated neighborhood in the southside of Chicago, then how a system of stereotypes and preconceived notions prevented him to be on an equal playing field when going to college. Next how he had to go above and beyond the normal expectation of a black youth because according to him “as black men we allow ourselves to set low standards, because of the things we have to go through success for us is just making it out”.

Dr. Derrick Brooks through personal experience shows why and how black people are put into a box of what they can and can’t accomplish. Preconceived notions prevent unbiased opportunities and systematic stereotypes create assumptions about the black life that are null and void. Thus, being the root of the black college experience and ultimately the black experience which is widely based on the image created by those who have never been a part of the black experience. In addition, forming the categories set aside to group African Americans such as lazy, hood rats, at risk, etc. which takes a toll on the life of a black American. Despite what is assumed the educational success of black people cannot be in comparison to any other simply based on its uniqueness due to what they have and still do go through in order t make it in not only school but life itself. The theme of this program is significant to the understanding of African American history because the box created to hold African Americans is a piece of the puzzle in the story of the black life.

Works Cited

College Dropout Rates [2023] – US Statistics and Data. 5 Mar. 2021, www.thinkimpact.com/college-dropout-rates/#:~:text=For%20full%2Dtime%20four%2Dyear.

Deborah Gray White, et al. Freedom on My Mind : A History of African Americans, with Documents, Boston New York Bedford/St. Martins, 2017.