Intending to share information and knowledge on Black History, Dr. Brooks, at the University of San Diego, presented on ghostly ideals and the hauntology of race and religion. This event was a meeting in which viewers discussed with Dr. Brooks and asked questions when they had arisen. Not only did the presentation allow for an understanding of race and religion, but it also discussed the hauntings of gender inequality. He talked about the idea of hauntology and how it related to religion, while Professor Babka, from the theology department at USD, offered her insight on the topic. Black male clerical power has plagued the genealogy of black religious leadership in socio-political life. As they relate to social issues, sexism, and challenges within the church, these themes are entwined with society and African American history while showing through in the criminal justice system. While introducing this topic, Brooks notes that the term hauntology comes from social violence that makes itself known. This interconnection between social issues can be shown and presented through hauntology. This idea is built upon by a social ghost where something is barely visible but makes itself known in less prevalent ways. Like a ghost, it haunts and draws effectively. These ideas and forces that one usually tries to ignore but never leaves them alone. But, by investigating these ghosts, we can turn destructive hauntings into something more empowering. As we dive deeper into African American history, it is crucial to note the hauntology that has occurred in the past and how it has affected issues in our society today.

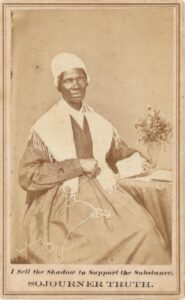

Black feminist  hauntology is an analysis of time that captures the continual nature of structural violence, not just symbolic or theorized violence that is racial colonialism. This haunting has taken over Black freedom. As these ideas present themselves through interconnection, we can see it prominently through history as people of color and women were at a point where they faced discrimination. These ideas are discussed in Freedom on My Mind as we can see that Black oppression ties itself to multiple layers of problems and “While black men searched for more satisfying ways to express their manhood, black women formed new organizations to fight racism and sexism” (White, 996). Many women of color became exposed to the negative impact of being a Black female in a society where neither was accepted. As people looked down upon Black women, they refused to accept this fate and continued to work at changing this societal norm. Furthermore, “Other black feminist groups were established in the late 1960s and early ’70s. The National Black Feminist Organization, the National Alliance of Black Feminists, the Combahee River Collective, and Black Women Organized for Action all emerged in response to the black freedom movement, which they felt excluded them, and the new women’s rights movement, which likewise neglected their particular issues. Over and over, they reiterated the concept of double jeopardy — “the phenomenon of being Black and female, in a country that is both racist and sexist.” (White, 970). They contended that all Black people must fight on several fronts at the same time, and they challenged white feminists to make racism and classism women’s problems. Black females fought against white supremacy and challenged racial oppression. As the Great Depression furthered Black marginality, visions of freedom expanded. As they worked to change patterns of oppression, this lies evident. The presentation allows students to understand how male supremacy tormented females in society.

hauntology is an analysis of time that captures the continual nature of structural violence, not just symbolic or theorized violence that is racial colonialism. This haunting has taken over Black freedom. As these ideas present themselves through interconnection, we can see it prominently through history as people of color and women were at a point where they faced discrimination. These ideas are discussed in Freedom on My Mind as we can see that Black oppression ties itself to multiple layers of problems and “While black men searched for more satisfying ways to express their manhood, black women formed new organizations to fight racism and sexism” (White, 996). Many women of color became exposed to the negative impact of being a Black female in a society where neither was accepted. As people looked down upon Black women, they refused to accept this fate and continued to work at changing this societal norm. Furthermore, “Other black feminist groups were established in the late 1960s and early ’70s. The National Black Feminist Organization, the National Alliance of Black Feminists, the Combahee River Collective, and Black Women Organized for Action all emerged in response to the black freedom movement, which they felt excluded them, and the new women’s rights movement, which likewise neglected their particular issues. Over and over, they reiterated the concept of double jeopardy — “the phenomenon of being Black and female, in a country that is both racist and sexist.” (White, 970). They contended that all Black people must fight on several fronts at the same time, and they challenged white feminists to make racism and classism women’s problems. Black females fought against white supremacy and challenged racial oppression. As the Great Depression furthered Black marginality, visions of freedom expanded. As they worked to change patterns of oppression, this lies evident. The presentation allows students to understand how male supremacy tormented females in society.

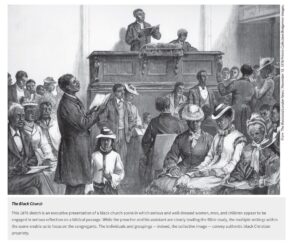

Further, society has misunderstood the idea of religion and churches, which leaves people with a preconceived notion about Black religious people. In order to better understand, we can connect these ghostly ideas to “Black Theology in American Religion” and “Race, Religion, and Beliefs about Racial Inequality” which talk about the importance that religion has had on the Black community.  Because religion is so deeply segregated along racial lines, most white Americans are unfamiliar that “The church has long been a central institution in the lives of Black Americans, serving as an important social, economic, cultural, and political resource” (Taylor). One often understands Christian theology, but Babka speaks about Black religious thoughts differing from the Christian theology of white Americans, nor does it directly relate to traditional African beliefs. One must note that it is both, but adapted to the situation of Black people. They resorted to Black religious ideas as they sought justice in a country ruled by a white ideology in its social, political, and economic systems. African Americans were enabled to look through distortions of the gospel and realize the actual meaning of God’s deliverance of the oppressed. It is through these ideas that we can understand the importance of religious aspects in African American history. As people leaned toward religion, they were not welcome in a traditional white church and in turn, were able to make Black communities. These communities and churches brought people together, and “Five themes in particular defined the character of black religious thought during slavery and its subsequent development: justice, liberation, hope, love, and suffering” (Cone, 756). Black people depended on their community and found hope in following God. Even though white people were preaching that the church was unavailable to them, they pushed beyond these hauntings and followed God anyway.

Because religion is so deeply segregated along racial lines, most white Americans are unfamiliar that “The church has long been a central institution in the lives of Black Americans, serving as an important social, economic, cultural, and political resource” (Taylor). One often understands Christian theology, but Babka speaks about Black religious thoughts differing from the Christian theology of white Americans, nor does it directly relate to traditional African beliefs. One must note that it is both, but adapted to the situation of Black people. They resorted to Black religious ideas as they sought justice in a country ruled by a white ideology in its social, political, and economic systems. African Americans were enabled to look through distortions of the gospel and realize the actual meaning of God’s deliverance of the oppressed. It is through these ideas that we can understand the importance of religious aspects in African American history. As people leaned toward religion, they were not welcome in a traditional white church and in turn, were able to make Black communities. These communities and churches brought people together, and “Five themes in particular defined the character of black religious thought during slavery and its subsequent development: justice, liberation, hope, love, and suffering” (Cone, 756). Black people depended on their community and found hope in following God. Even though white people were preaching that the church was unavailable to them, they pushed beyond these hauntings and followed God anyway.

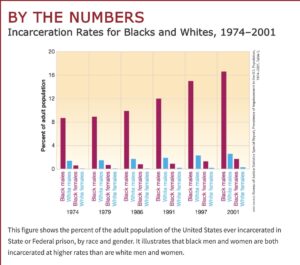

Furthermore, “Black Feminist Hauntology” states that we must also realize the attack that the criminal justice system places on Black people. People understand the longing to, “abolish the criminal justice system because it is rooted in state sponsored violence and revenge” (Hanna, 55). But, fail to acknowledge it on the basis that in order abolish the system, they must accept racism as the fuel that keeps the criminal justice system moving. It is clear that the racializing and colonial roots of the criminal justice system cannot be addressed just by deconstructing crime and delegitimizing the use of state violence in the system. When these individuals are highlighted by the committed crime, it allows for segregation. By doing so, it reinforces the idea that they are the result of personal dysfunction rather than a system. According to hauntology, this violence has only been out of control since it was taken and warped to involve this kind of violence. Thus, “The relationships between colonial slavery and criminal justice violence are inevitable and unavoidable” (Hanna, 60). Our perceptions of this dangerous few are plagued and caught in an endless cycle of racist absurdity. Because the justice system was effectively closed as an avenue to reinstate affirmative action or challenge the mass incarceration of African A mericans, we see that the incarceration rates for Black people compared to white people were dramatically different, most being Black males. These issues are still prevalent today. The judicial system was essentially closed as a means of reintroducing affirmative action or challenging the widespread imprisonment of African Americans. As one can learn more about each aspect of change that was occurring, it can become easier to understand how everything was connected and how every act against Black people led to a nation where racial segregation was present.

mericans, we see that the incarceration rates for Black people compared to white people were dramatically different, most being Black males. These issues are still prevalent today. The judicial system was essentially closed as a means of reintroducing affirmative action or challenging the widespread imprisonment of African Americans. As one can learn more about each aspect of change that was occurring, it can become easier to understand how everything was connected and how every act against Black people led to a nation where racial segregation was present.

The necessity to eliminate white supremacist hetero-patriarchy is at the core of all battles since, without the demise of these pillars, colonialism would continue to exist in manifestations and progressively poor apparitions. Black hauntology brings back into view the chains that link racial colonialism and slavery to the lives and deaths that involve Black people. This lingering idea prompts the understanding of African American History by bringing light to how racism and sexism are present throughout history and how they apply to issues revolving around the church and criminal justice system. The presentation commemorates Black history as Brooks explains the ideology of hauntology while also addressing the means of what must be done to further clarify and add to these ideas. As we question what is next, it is clear that Black Americans have problems that must address this double reality. In an act to get rid of racism and segregation, we must notice that racial colonialism reemerges in hauntology as an oppressive system of power and control. A system that is based on white supremacist ideas about humanity and conquest must continually return in different forms to maintain its lies. To move forward, one must fully understand that these cases of anti-Black oppression can be tied to hauntology. In the past, hauntology was hidden, but now it shapes the present and Black future by recognizing these realities and using this knowledge to prompt a world that is not haunted by white people’s actions. In doing so, it gives Black people back their freedom and empowers people to use strength rather than weakness to combat oppressive patterns.

Works Cited

Cone, James H. “Black Theology in American Religion.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 53, no. 4, 1985, pp. 755–71. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1464274. Accessed 9 May 2023.

Saleh-Hanna, Viviane. “Black Feminist Hauntology.” Champ Pénal/Penal Field, 23 Mar. 2015, journals.openedition.org/champpenal/9168.

TAYLOR, MARYLEE C., and STEPHEN M. MERINO. “Race, Religion, and Beliefs about Racial Inequality.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 634, 2011, pp. 60–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29779395. Accessed 9 May 2023.

White, Deborah G., et al. Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents. Bedford/St. Martins, 2021.