Rationalizing Religion and Modernity

Out of the many black history events held this year at USD, I eventually decided the program I would like to attend would be Candice Marie Benbow’s Red Lip Theology Seminar sponsored by the USD Copley Library and San Diego Public Library. Through the course of the speech, Candice Benbow narrates her experience growing up in a feminist Christian family. Candice demonstrates through the narration of her experiences the lack of understanding the church often had for her and her family. She shares her disillusionment with the church over the years but details how she has not lost her faith and remains a Christian. She encourages the audience to think critically and make sure to question all beliefs. One should understand why it is they believe something before fully subscribing to any idea. Benbow ultimately expresses that the modern black church is losing modern black women and that it must adapt to become a more welcoming and inclusive environment. The program’s message of taking action to make real change in the world resonates with the “Black Freedom Struggle” and expands one’s understanding of African American History. This is because African Americans have always been the ones to take control of their fate and fight against the shackles of oppression.

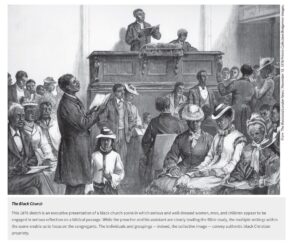

The first thing I would like to talk about is the role of the black church in early African American history. Even with all the negative aspects of the church Candice brought to light it is important to acknowledge that the church was one of the first outlets African Americans had for expressing any form of freedom. It was the church that originally brought African Americans a community that they could feel accepted in. The abolitionist movement, which aimed to abolish slavery and protect African Americans’ freedom and rights, was fundamentally influenced by the Black Church. African American activists and leaders like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman were given a platform to inspire their people and rally support for the battle against slavery. The Church acted as a hub for protest planning, literature distribution, and gatherings to discuss and advance the abolitionist cause.

African Americans benefited from the Black Church’s cultural and spiritual empowerment in addition to its political and social activism. African customs have been preserved, and they have been combined with Christian teachings to produce a distinctive and vivacious religious experience. The Black Church gave birth to gospel music, which is known for its beautiful melodies and impassioned sentiments. This strong form of cultural expression gives people suffering hardships courage, hope, and inspiration. Freedom on My Mind Chapter 9 even brings to light the fact that “Joining a church was an act of physical and spiritual emancipation, and black churches united black communities.” This appreciation for the church is shared by Candice Benbow herself as she believes that even in the present day the church should be a place black people can feel accepted and free in. She states “Give us room to live, and be, and thrive, and grow, and flourish.” Candice believes that when African Americans are given room to flourish the world will flourish along with them. Candice calls out the church’s mistakes not because she wants it to burn but because she wants it to be better. She wants it to serve the same purpose it served long ago for those who needed it the most.

The Black Freedom Struggle is a concept that has existed since the beginning of black enslavement. Throughout the course of African American History, black people have always been fighting against their oppressors. It was understood from very early on that the only way black people would ever be able to attain freedom is if they fought for it. This struggle can be seen in many ways depending on what era of history is being examined. It was seen when African Americans decided to fight in the War of Independence in hopes of achieving emancipation. It can be seen in the various slave revolts during the 18th and 19th centuries. It can even be seen in the modern day with many African Americans today still striving for true equality in all aspects of life. This struggle is often overlooked, and many believe it was the “white savior” who truly freed African Americans. This viewpoint fails to take into account all the hard work and sacrifices that have had to be made by black people to get as far as they have come. The Civil Rights Movement made progress, but the fight for racial equality is ongoing. The Black Freedom Struggle is still evolving, tackling new challenges, and pushing for social and economic justice. The Black Lives Matter movement, sparked by the deaths of unarmed black individuals at the hands of law enforcement, is renewing the fight against systemic racism and police brutality.

The article “Strategic Sisterhood: The National Council of Negro Women in the Black Freedom Struggle by Rebecca Tuuri” brings to light the efforts of The National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and how this group helped fight against injustice during the Civil Rights era in the 1960s and 1970s. This group was one of the first organizations to strive for an end to both racism and sexism in the United States. The NCNW understood the value of encouraging women to speak up for themselves and effect change by amplifying their voices. They encouraged African American women to participate in politics, leadership positions, and public service through its Women in Public Life program. Conferences, workshops, and training sessions were conducted by the NCNW to provide women with the knowledge and abilities they needed to be effective leaders and champions in their communities. The NCNW has survived and evolved in the face of changing socioeconomic problems.

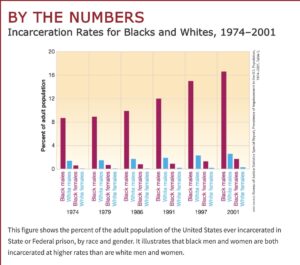

Racial and gender inequality is still a problem, so they continue to confront it by promoting laws that support and empower African American women and their families. The organization’s programs now cover topics like systematic racism eradication, criminal justice reform, and health inequalities. This organization has made tremendous contributions to the civil rights movement. The movement in and of itself is a demonstration of African American perseverance and strength. The movement represents what Candice preaches in her speech very well. If you want to see change then you must take action. Sometimes the only way to achieve this is to go against authority and rebel against the status quo. This defiance is similar to the defiance Benbow displays against the Baptist church. In order to improve something sometimes you must take that something apart and rebuild it with new pieces. If the institution itself is flawed, then it must be deconstructed and changed intrinsically.

The Church should be an outlet for black expression and should never serve to shame or make its congregation uncomfortable. Candice Benbow emphasizes that the black freedom struggle should be valued above all else and that one should always be analytical regarding their most important beliefs. She preaches against indoctrination and encourages one to cultivate the individual. She calls the audience to ask themselves who they truly are and who they want to be in the future. The black freedom struggle is integral to understanding African American History as it is the main force that has propelled it forward. It is thanks to the centuries of struggle and battle brought upon by black people in the United States that a more equal society has been reached. This struggle will rage on and will continue until true equality has been reached.

Works Cited

CHAPTER 9 Reconstruction: The Making and Unmaking of a Revolution, Freedom on My Mind, Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin Jr.

Strategic Sisterhood: The National Council of Negro Women in the Black Freedom Struggle by Rebecca Tuuri (review) Sariah Orocu Alabama Review, Volume 74, Number 3, July 2021