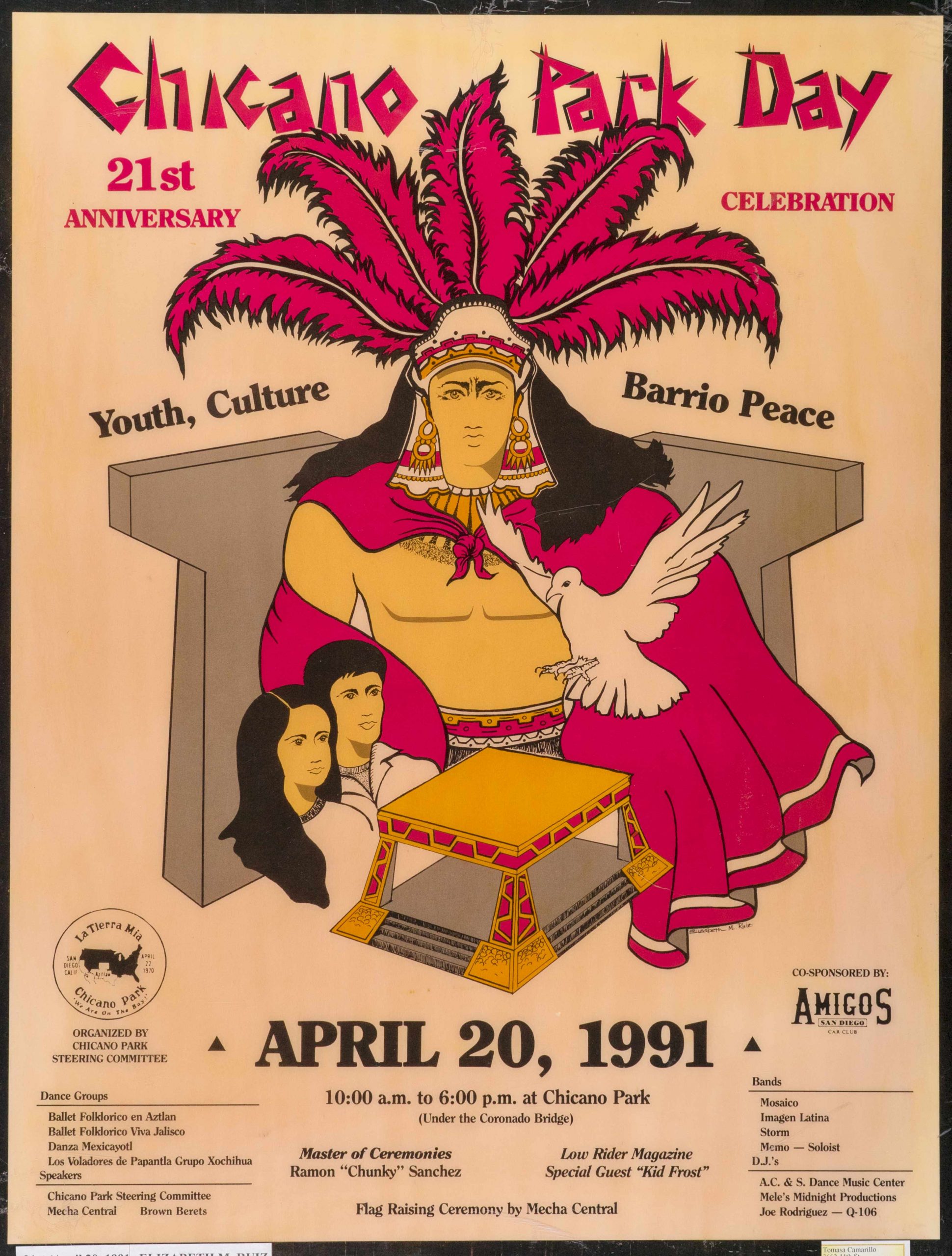

For Chicano communities throughout San Diego, Chicano Park embodies not only a space for exemplification of place and culture, but resistance as well as the space was not given to them, but instead fought for in the face of infrastructure and land dispossession. Each year around April 22nd, Chicano Park Day celebrates this takeover as an assertion of presence and self-determination for Chicano communities. The 1991 poster created for Chicano Park Day highlights youth, culture, and peace within the barrios, which can be best embodied by communal contexts and Logan Heights’ love for music. Rigo Reyes, a community scholar and activist, explained in an interview how gang violence was prominent during this time due to dominant media influences perpetuating feelings of otherness and instances of self-fulfilling prophecies. Reyes described how experiences of double consciousness and simultaneous exclusion from Mexican communities and white culture resulted in a necessitated “third space,” in which many youth formed their own groups, proud to represent their communities. However, rejection from not being “Mexican enough” but not “white enough” caused media outlets to portray these groups as other, concretizing socially constructed labels of danger. The groups slowly began to succumb to these negative perspectives and fulfill communal expectations of violence. This resulted in 1991 Chicano Park Day being a celebration of finding and creating identities, youth with tremendous potential, and embracing differences through culture and music.

Music is at the heart of the community, it has the ability to create solidarity and unity as well as express the struggles and joys of life. During the 1990s, many young Mexican Americans utilized this art form for self expression and community engagement. For the youth, expression through rap was one of the primary mediums and as it developed in Los Angeles, it quickly moved into “other urban areas. Led by Low Profile Records and its roster of Chicano rappers, San Diego boasts the second largest Chicano rap scene”(Candelaria 348). Logan Heights was at the center of this Chicano rap movement, especially among the youth and even though there was existing tensions within the community, everyone was able to come together to enjoy this music. Often these Logan Heights Chicano rappers used this art “to comment on important issues in their communities. They rap about love, parties, gangs and gang violence, police corruption and abuse, poverty, family, drug use and abuse, the education system, and world politics”(Candelaria 349). Music was a true medium for expression of experiences of oppression and violence but also important to the community. During our interview with Rigo Reyes, he spoke to the fact that each generation has different forms of music and culture, like his Oldie music and lowriders, to work on understanding identity and communal struggles. Even though each generation expresses differently, songs like Chicano Park Samba are unifying for all generations and truly speak to their identity, culture, and experiences.

Popular culture is at the intersection of conflict and music, and for young Chicano people living in Logan Heights, this form of self expression led to understanding, community, and awareness of social issues. We continue to see this trend today where artists speak to their experiences of institutionalized racism, oppression, sexism, and violence that deeply impact communities. For example, African American rapper, Kendrick Lamar, produces music that also aims to address societal issues while building solidarity and community around experiences. Issues like police brutality, drug use, domestic violence, prison industrial system are topics Kendrick focuses on inorder to bring them to the forefront of mainstream conversation and create representation. This is what artists like Lil’ Rob, Royal T, Sancho, Knightowl, and many more were San Diego rappers who were part of this movement of rap as a platform to address issues like gang violence (Candelaria 348).

Candelaria, Cordelia Chávez. Encyclopedia of Latino Popular Culture. Edited by Arturo J

Aldama et al., vol. 1, Greenwood Press, 2004.

Written by Emily Beck and Chloé Leclair