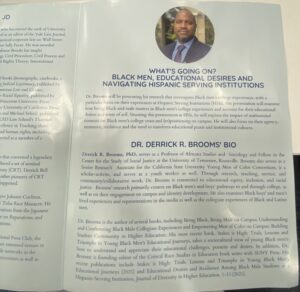

About a year ago in April 2022, the Humanities Center at USD held an online presentation featuring Alexis V. Jackson and her poetry collection, My Sister’s Country. Along with Jackson, Dr. Channon Miller and Dr. Farah Jasmine Griffi joined for the discussion of her poetry collection. This presentation allowed the audience to examine the personal experiences of African-Americans, both past and present, that others outside of the African-American community could not understand. Jackson’s poetry collection not only includes her own profound work but also possesses Zuihitsus, a type of poetry that collages pieces of other’s work to create a poem in response to one’s own surroundings. Her pieces of Zuihitsu include fragmented pieces of the voices of other African-American women, creating a platform to elevate the voice of Black women to show their collective experience and not just hers.

Jackson’s presentation of her poetry work “My Sister’s Country” is significant to our understanding of African American history because her poems demonstrate the enduring impact of past experiences, revealing how they continue to reverberate in the present and shape the lived realities of Black individuals in America. In art and cultural movements, we see throughout history that poetry became a way to express the complexities of Black identity, explore racial pride, challenge stereotypes, preserve African culture, and critique social and political issues. Poetry provides an outlet for African-Americans to share their lived experiences, perspectives, and emotions in their own words.

When tracing the origins of African-American poetry, we find its roots deeply intertwined with Africa’s ancient oral traditions that predate the era of slavery. This consisted of storytelling, proverbs, folklore, legends, and many other forms. These are “…kept alive by being passed on by word of the mouth from one generation to the next” (Hamlet, 74). Oral communication and the use of language have always been one of the dominating features of African culture. It is said that “The people’s cultural mores, values, histories and religions were transmitted from generation to generation by elderly individuals… who were known to be excellent storytellers” (Hamlet, 74). However, when the slave trade began in the fifteenth century, African culture underwent significant transformations as enslaved individuals were forcibly separated from one another by slave traders. This restricted all forms of communication among enslaved people. While the purpose of this isolation was to suppress rebellions, its additional consequence stifled African and African-American voices, thereby preventing the passing down of traditional culture across generations. By incorporating elements of African storytelling into their poetry, both past and modern-day African-American poets maintain a connection to their ancestral traditions and convey the richness of African and African-American cultures. It provided an opportunity for African Americans to reclaim elements of their culture that had been appropriated or eroded by the dominant white society, while also preserving the remaining aspects of their heritage that could be passed down to future generations.

African-American poetry started to form rapidly during the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that used art to express African-Americans politically and socially. While many forms of art emerged from this movement, poetry was one of the most pivotal components, especially with the importance of oral tradition within many African cultures. Most of the poetry during the Harlem Renaissance had the intention of reaching out to the white audience. By seeking the attention of white audiences, poets aimed to challenge the prevailing stereotypes, prejudices, and marginalization that African-Americans faced in society. White readers were invited to empathize with these experiences, fostering a greater understanding and promoting dialogue and solidarity across racial lines. However, some viewed that poetry and other art should only be used for political advantage. For example, “Du Bois had insisted that ‘all Art is propaganda,’ by which he meant that art should deal with subjects that would advance the black freedom struggle” (White et al., p. 1173). Others thought that poetry should be directed at a more integrationist approach rather than separatist. Regardless, poetry emanating from both perspectives exerted a significant influence. Additionally, Fire!!, an African-American magazine dedicated to the cultural art movement, “…would embrace the lower classes and the gritty realities confronting blacks, not just genteel, middle-class concerns” (White et al., p. 1173). Poetry provided African-Americans with a powerful medium through which they could authentically express their raw, unfiltered, and often harrowing experiences.

One of the most notable poets of the Harlem Renaissance was Langston Hughes. Hughes played a crucial role in popularizing African-American poetry and making it accessible to a broader audience. His poems were published in mainstream magazines, newspapers, and literary journals, reaching readers beyond the confines of the Harlem Renaissance. By bringing African-American poetry into the mainstream, Hughes helped to challenge the notion that African-American literature was only of interest to a niche audience, paving the way for future generations of African-American poets to gain recognition and acclaim. It also defeated the stereotype that African-Americans were intelligently inferior.

My Sister’s Country is a great modern-day example of how African-American poetry has developed over time to become a significant cultural influence in America. Poems from Jackson’s collection include both past and present-day components of African-American culture: lyrics from modern-day black singers, references to proverbs and religion, and references to how the slave trade and oppression against African-Americans have shaped the lives of the African-American community today. Her poems specifically depict a deep level of emotion that allows others to humanize African and African-American experiences. Unless you are African-American yourself, people can’t fully comprehend the severity of how the slave trade and racism affected African-Americans and their families, even to this day. Poetry serves as a channel for evoking and eliciting emotional responses from readers, endeavoring to communicate personal experiences with the intention of creating a rapport grounded in connection and understanding. My Sister’s Country also promotes intersectionality and makes mention of the stereotypes that African culture has also conducted, such as in the poem “My Sister’s Country” when Jackson mentions small details such as saying “Here, it is criminal for men to make breakfast” (Jackson, 23). African-Americans were once largely viewed as one-dimensional, but Jackson’s poetry illuminates the multifaceted nature inherent within the African-American experience. It highlights that African Americans do not have a singular or homogeneous experience but face a range of intersecting social, economic, and political factors that shape their lives. It recognizes the complexity of individual identities and experiences, debunking the notion that all African Americans share identical perspectives, struggles, or achievements. This helps eliminate stereotypes that all African-Americans are inherently the same and contributes to the elimination of stereotypes that preserve the idea of homogeneity of African-Americans, recognizing the great amount of diversity within the community. In the poem “Therapy Session Number 19”, there are also mentions of the additional challenges of being an African-American woman such as “…trying to normalize the word vagina. And the habit of blaming systems over individuals” and “…only [drinking] coffee when dieting” and “I hate having a body” (Jackson, p.60). These are just very few of the multiple references she makes throughout her poetry collection of being not only the experiences of being African-American but a woman as well. African-American poetry is a great way to promote intersectionality not only for themselves, but for other minorities around the world too.

The narratives and themes of African-American poetry are significant as they provide authentic voices, humanize the African-American experience, challenge stereotypes, inspire resistance, and offer cultural and historical context. They contribute to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of African-American history by centering African-Americans’ perspectives, struggles, and triumphs. Jackson’s “My Sister’s Country” exemplifies the evolution of African-American poetry, incorporating elements of contemporary black culture, religious references, and reflections on the lasting impact of the slave trade and oppression. Ultimately, African-American poetry, as exemplified by Jackson’s work, serves as a channel for evoking emotional responses, bridging gaps of understanding, and challenging societal narratives. It allows African-Americans to share their lived experiences, perspectives, and emotions in their own words, reclaiming their voices and preserving cultural heritage. By engaging with African-American poetry, we gain valuable insights into African-Americans’ historical and contemporary struggles, triumphs, and complexities, contributing to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of American history and culture.

Works Cited

White, Deborah G., et al. Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans With Documents. Bedford/St. Martins Macmillan Learning, 2021.

Hamlet, Janice D. “Word! The African American Oral Tradition and Its Rhetorical Impact on American Popular Culture.” Black History Bulletin, vol. 74, no. 1, 2011, pp. 27–31. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24759732. Accessed 11 May 2023.

Jackson, Alexis V. My Sisters’ Country. Kore Press, 2022.

Red Lip Theology is a call to action for Black women to use their voices and take up space in their religion and culture. The name “Red Lip Theology” Is inspired by the symbol of red lipstick, which represents both femininity and boldness. “Men dominated church leadership, but women constituted most of the members and regular attendees and did most of what was called church work. Women gave and raised money, taught Sunday school, ran women’s auxiliaries, welcomed visitors, and led social welfare programs for the needy, sick, and elderly. They were also prominent in domestic and foreign missionary activities. One grateful minister consistently offered “great praise” to the church sisters for all their hard work” (White, Bay & Martin, 2021). Benbow asks herself the question,“What is owed to black women for that level of religiosity, what is owed to black women for that level of commitment?” where she answers, “Red Lip Theology was and is my way of trying to make sense of that.”

Red Lip Theology is a call to action for Black women to use their voices and take up space in their religion and culture. The name “Red Lip Theology” Is inspired by the symbol of red lipstick, which represents both femininity and boldness. “Men dominated church leadership, but women constituted most of the members and regular attendees and did most of what was called church work. Women gave and raised money, taught Sunday school, ran women’s auxiliaries, welcomed visitors, and led social welfare programs for the needy, sick, and elderly. They were also prominent in domestic and foreign missionary activities. One grateful minister consistently offered “great praise” to the church sisters for all their hard work” (White, Bay & Martin, 2021). Benbow asks herself the question,“What is owed to black women for that level of religiosity, what is owed to black women for that level of commitment?” where she answers, “Red Lip Theology was and is my way of trying to make sense of that.”