Strange Fruit and Scholars

Strange Fruit is a fictional screenplay written and directed by Alanna Bledman. Her screenplay was first performed at the University of San Diego in the Black Box Theatre in February 2020.

The University of San Diego is a private, 4-year University in San Diego, California. The Black Box Theatre hosts various screenplays and showings from theatre students year-round.

The narrative entails a group of students who are entering their first year of college. Despite their different personal struggles, they are brought together by a collective struggle in being black students at a predominantly white university. Historically, black students in America have been barred from entering and achieving success in academia. Strange Fruit highlights this struggle as continual for black students surviving in a system designed for them to fail—understanding the narrative of Strange Fruit aids in explaining why such a large portion of the freedom struggle centers on achieving equality in education.

Throughout the screenplay, the students deal with multiple racist encounters on campus. Finally, deciding that they had had enough, the students complained to their Dean. When they agreed to attend the school, the students were under the impression that the school was committed to diversity and inclusion. To their surprise, the Dean does not make an effort to help. After this incident, they become wary of the school’s promises. So, the students begin to investigate the history of their school and learn of the sick, chilling truth. They discover that the university grounds were the site of a massacre of freed black people who were murdered by their former masters after the Civil War. They also learn that the Dean is the ghost of the slave-owner founders. When the students confront them, the Dean reveals that the school entices black students into attending the school so that they can murder them.

While Bledmen frames the screenplay as a thriller, the paranormal activity is not the scary part of strange Fruit. What is scary about this screenplay is that their experiences reflect the reality of the black students in higher education. Strange Fruit focuses on the ugly truth about the education system: it excludes black people. In the Reconstruction period, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, or HBCUs, were founded by black institutions such as mutual aid societies and African churches. These facilities offered access to education that was otherwise unavailable to black students. The goal was to instill self-reliance and create an educated, successful generation of black students who might have a chance in the freedom struggle. The curriculum at Hampton Institute, for example, was created so that black students could pull themselves up by their bootstraps and win their freedom by earning respect from white Americans (Freedom on my Mind, 310.) While some black Americans did achieve a degree of economic independence, their education did not stop white Americans from preventing black Americans access to their civil rights. Segregation would only become more stringent and legal post-reconstruction. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy V. Ferguson in 1896 only helped to cement segregation’s legality in the education system.

Continuing into the Jim Crow and the Civil Rights era, black students continued to struggle against segregation. In 1965, Congress passed 20 USC 1060, a federally funded program dedicated to aiding institutions whose goal was to educate black Americans (Abelman 105.) Though educating black Americans was not Congress’ intention. In reality, it was a way to circumvent the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in schools. HBCUs provided a safe space for black Americans to learn and achieve success in their fields, so many black students chose to attend them. Those who were able to gain access to white institutions did so utilizing the court system and their perseverance.

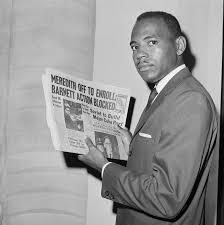

James Meredith, the first black student at the University of Mississippi, had to fight through the courts to achieve admission to the University in 1962.As examined by Professor Frank Lambert at Purdue University for the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, in the following year, another black student Cleve Macdowell had to fight through the courts as well (Lambert, 58.)

A photograph of James Meredith is depicted to the left holding a newspaper describing his historic enrollment.

Although they were both initially admitted, the University attempted to rescind their admission because they were black. It was not until 1964 that a black student, Irwin Walker, at the University did not need to seek a court order. (Lambert, 59.) During this time, though, the few black students on campus received a variety of abuses. In Cleve Macdowell’s case, he lived on a floor alone because no white person wanted to live near him. His harassment became so severe that he felt the need to carry a gun for his protection. (Lambert, 59.) When the University discovered his weapon, the University expelled Macdowell. Professor Lambert further explains that when Walker received a funeral wreath on his dormitory door, the University failed to respond (Lambert, 59.) The experiences of these students are not an anomaly. Black students throughout America have experienced racism in academia, and many times the University has protected the oppressor. The history of universities protecting black oppression is at the core of the discussion in Strange Fruit.

Strange Fruit, while being a work of fiction, highlights the struggles of black students. Like James Meredith and the other students at Ole Miss, the students in Strange Fruit experience racism that is not only protected but condoned by the University. In both cases, while the University claimed to support diversity, they did nothing to support their black students. By not punishing the white oppressors, the University condoned their racist actions. Set in 2020, Strange Fruit highlights how this is an ongoing struggle in the academic world. In 2016, the University of Missouri black student enrollment rate dropped 42% from the previous year following the University’s President’s handling of racist incidents (Rao.)

The image on this page is a picture taken during the University of Missouri football strike in 2015. The image, sourced from ColorLines is as follows, “University of Missouri football coach Gary Pinkel posted this picture during the strike with the following caption: “The Mizzou Family stands as one. We are united. We are behind our players. #ConcernedStudent1950 GP” Photo Credit: Gary Pinkel via Twitter.”

The predominantly black football team went on strike, which ultimately resulted in the President’s resignation. Republican state representative, Rick Brattin, responded to their protest with a bill that would not only fine staff for allowing teammates to protest, but also revoke their scholarships (Rankin.) Because of cases like Mizzou in 2015, many black students will continually choose to attend HBCUs as opposed to other institutions. At HBCUs, black students know that their race will not determine nor threaten their level of success and prosperity.

A collection of HBCUs that receive federal funding.

Understanding the struggle of black students in academia is essential for understanding African American history as a whole. Black Americans have been prevented from achieving full political, social, and economic equality in the United States. Restricted access to education is just one of the many factors that keep racist power structures in place. Students will continue to struggle to succeed in a system designed with their exclusion in mind. Strange Fruit strips away the pretty admissions packets and reveals the dark reality of academia in America.

Works Cited

Abelman, Robert, and Amy Dalessandro. “The Institutional Vision of

Colleges and Universities.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 40, no. 2, 2009, pp. 105–134. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40282625. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

Elliot, Debbie. “James Meredith.” Integrating Ole Miss: A Transformative, Deadly Riot, Npr, 1 Oct. 2012 www.npr.org/2012/10/01/161573289/integrating-ole-miss-a-transformative-deadly-riot.

Lambert, Frank. “The Black Students Who Followed in the Footsteps of James Meredith at Ole Miss.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 66, 2009, pp. 58–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20722175. Accessed 29 Apr. 2020.

McCambridge, Ruth, et al. “New Legislation Aimed at Increasing Federal Grants and Contracts to HBCUs.” Non Profit News | Nonprofit Quarterly, 22 Feb. 2019, nonprofitquarterly.org/new-legislation-aimed-at-increasing-federal-grants-and-contracts-to-hbcus/.

“Medallion.” University Marks and Logos, University of San Diego, www.sandiego.edu/brand/visual-identity/logos/.

Rankin, Kenrya. “ICYMI: Missouri Rep Introduces Bill to Revoke Scholarships of Protesting Student Athletes.” Colorlines, Race Forward, 5 Jan. 2016, www.colorlines.com/articles/icymi-missouri-rep-introduces-bill-revoke-scholarships-protesting-student-athletes.

Rao, Sameer. “Black Enrollment Falls at Mizzou Following Anti-Racism Protests.” Colorlines, Race Forward, 18 July 2017, www.colorlines.com/articles/black-enrollment-falls-mizzou-following-anti-racist-protests.

“Reconstruction: The Making and Unmaking of a Revolution.” Freedom on My Mind: a History of African Americans, with Documents, by Deborah G. White et al., Bedford/St. Martins, 2017, pp. 310–311.