Sam Jorgenson

Dr. Channon S. Miller

HIST-128-01

12 May 2023

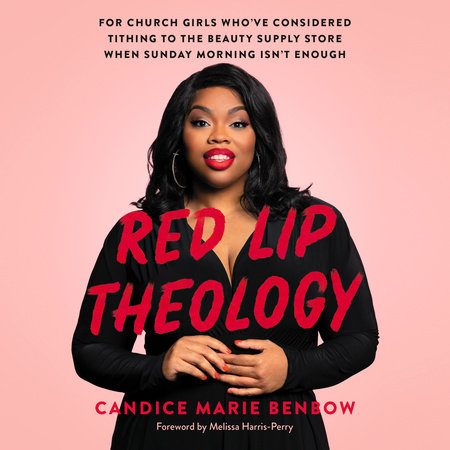

Red Lip Theology Blog

On February 27th, 2023, I traveled to the Copley Library to hear author and theologian Candice Marie Benbow speak about her book, Red Lip Theology. In this collection of essays, Candice explores topics such as faith, identity, and authenticity. Her goal is to give black women who feel unsupported or isolated from the Church a voice by sharing her experiences growing up in the Black Church and how that has shaped the women she is today. She articulates her message using stories from her childhood, Black Church culture, and her journey beyond; to become a theologian. Her central statement is that the impact and influence of African American women in the Black Church have been underappreciated.

Candice was raised by her single mother with a strong emphasis on faith and femininity. She describes her mother’s situation, recalling that “as a single mother raising a Black girl during the height of the crack epidemic and the rise of gang violence, Mama believed the church would keep me safe” (Benbow, 2023). Her mother was a college professor, and she raised Candice with the same beliefs as herself. She always urged herself and Candice to push back against the norm of sexism that Black women experience throughout life, but especially in the Church. Her mother had very limited options, as many criticized her for becoming pregnant out of wedlock. Her mother was forced to stand in front of the Church and apologize for being pregnant, but refused as she felt no shame or regret for her pregnancy. However, the father, who was in the choir, was not expected to apologize or acknowledge the situation. This shows the disparity that existed between Black men and women in the Church, which plays an extremely influential role in Candice’s life. She remembers how the church and her family would make bets that she would “go off to college, become ‘buck-wild,’ get pregnant, and be forced to drop out. It would be years before I could see the projection behind their doubts about me, but as a child, I didn’t understand how people could be so mean” (Benbow, 9). Candice and so many young black children are exposed to racism in many different forms and at a much younger age than many realize. In Candice’s mothers’ case, even in the Black Church. The same Black Church that was built because previous invisible churches, or secret institutions where black people could practice faith and Christianity freely, stood strong and preserved by black women. Even now, black women are still living in spaces where they are taught to be inferior because of slight differences in family structures. In the introduction to her book, Candice recalls how the Black Church was planning a ceremony called “Hoody Sunday” to commemorate the murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin. Three days before “Hoody Sunday,” Rekia Boyd was murdered in Chicago by an off-duty police officer. Candice was told there was no mention of Rekia because she was a woman, and the pastors were “leaving it up to their respective youth and women’s ministries to honor her…The omission of Rekia from any institutionalized movement reinforced Black churches’ refusal to see the conditions and experiences of Black girls and women as the same as those of Black boys and men” (Benbow, XXIII). This frustration that Candice felt has the same roots of so many African Americans who struggled to understand why they were living in a country that didn’t support them. Why should Black men be drafted to fight in Vietnam when the country they’re fighting for doesn’t support them back? Why have Black women put so much effort in faith and the Black Church when they don’t receive that same effort back? The Church was all many Black girls had; a place where no mask had to be worn, and no racism was experienced. Most importantly, Candice’s mother never scorched the fire in Candice to ask questions about faith, no matter what the question was. She often asked her mother, “Do we owe the churches to change and push themselves to be the best they can be? How do we acknowledge the wrongs the Church has committed?” (Candice, 2023). She’s seen how the Black Church has treated her mother but doesn’t yet understand why.

After her mother died, Candice’s world fell apart. The connection she shared with her mother was deep and had profound effects on multiple aspects of her life. She began to struggle in college and with the Church, as praying and attending mass brought her too much pain. Her idea of faith had been so intertwined with her mother that when she died, her vision of faith felt much too hollow and inauthentic. As a result, she took a year and a half break from the Church to focus on grief and self-love. She describes how her college refused to give her a leave of absence three times because the death of her mother and her encounter with sexual assault wasn’t a valid enough excuse. She felt embarrassed and angry, as she felt they wanted her “to be like her ancestors who watched their loved ones die, be killed, or be sold off, and had no choice but to keep working in the fields while they mourned” (Benbow 68). She uses this comparison of her experience to her ancestors forced into slavery to reinforce the idea that Black women are disproportionately discriminated against in multiple areas of life. Even throughout the study of African American History, most of the famous names we hear, and study are Black men, even though Black women have had just as important of an impact on the Black Freedom struggle and in the Black Church. Throughout history, black women have “understood that their race, class, and gender intersected and reinforced one another. They were poor not just because they were female or because they were black but because they were both female and black” (Freedom on My Mind Chapter 16). This “double battle” has largely prevented black female voices from being heard or remembered, which is a shame because those voices are how we study the past and how those events have led to the present. The history of African Americans have been used to justify the racism and mistreatment they have encountered since the beginning of slavery, so it’s extremely important that Black women are heard too in order to create an accurate representation of African American History.

In this time away from the Church, she attended weekly Buddhist talks that explored topics of self-love and acceptance. These meetings created a shift in Candice’s mindset where she began to strengthen her relationship with herself. She realized that “removing the expectations and labels of God restored the faith and strengthened the relationship…God can take many forms, even ones that the Church may not consider “normal” or acceptable” (Benbow, 2023). She describes that, at the very core, Red Lip Theology is rooted in truth. It’s dedicated to giving women who are deeply faithful, but also different from the “norm” a connection where they feel related to, accepted, and strengthened by Candice’s story. She shares that she hopes the book will encourage other women to refuse to stand down against the racist and sexist ideas and beliefs that can control the Church in order to cultivate a space where everyone is welcome. She’s working for a future in which black women play a much larger role in the Black Church and have more influence in the world to come.

Sources :

Benbow, Candice Marie (2023, February 27). Red Lip Theology With Candice Marie Benbow [Speech & Book Signing]. Copley Library, Mother Hill Reading Room, University of San Diego, California.

White, D.G., Bay, M., & Martin, W.E. (2021). Freedom on My Mind, Third Edition: A History of African Americans, with Documents (Third Edition). Bedford/St. Martins. Gilkes, Cheryl Townsend (2023, November 1), If It Wasn’t For Women: Black Women’s Experience And Womanist Culture In Church and Community. First Edition. Orbis Books.