Red Lip Theology

Aleksa Caballero

HIST-128-02

Dr. Channon S. Miller

May 11, 2023

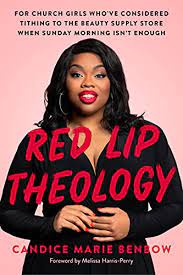

Red Lip Theology By Candice Marie Benbow

Candice Marie Benbow is an author, theologian, and cultural critic known for her work on black women’s spirituality, self-care, and self-love. She is the founder of Red Lip Theology, a movement that seeks to empower women to embrace their authentic selves and live fully in their purpose. She wanted to influence women to celebrate their identities, embrace their sexuality, and reject societal norms that may limit their full potential. Black women in faith are not known because their efforts are constantly pushed away or ignored, “Black women are never heralded as the forerunners of religious history ” (Benbow, 2023). This is important to acknowledge in African American History because as Benbow stated during the program, “Black women remain the most religious demographic in this country.” Black women in faith are yet another example of a group of African Americans who are and have been overlooked.

Along with her message, Benbow is able to explain her own story and share her personal experiences as a black woman who was active in African American church culture in the 1990’s. In Benbow’s writing and speeches, she has discussed how her mother’s strict religious beliefs and harsh parenting style influenced her own spiritual journey. She described her mother as a deeply religious woman who had strong beliefs from a young age. Benbow has also spoken about how her mother’s rigid interpretation of religious doctrine often left her feeling suffocated and trapped. She stated that her mother’s emphasis on obedience and fear of punishment made her feel like she was always walking on eggshells and never got to express herself or explore some of her own beliefs. Despite these challenges, Benbow has also credited her mother for giving her a strong foundation for her faith that has ultimately helped her in navigating her life. Benbow has stated that her mother’s influence had taught her the importance of having a personal relationship with God and seeking guidance from prayer and scripture. Overall, it is clear and important to note that Benbow’s relationship with her mother had a significant effect on her faith journey. While Benbow may have felt restricted at times, her mother’s beliefs helped her shape her understanding of spirituality and encouraged her to seek a deeper connection with God.

Red Lip Theology is a call to action for Black women to use their voices and take up space in their religion and culture. The name “Red Lip Theology” Is inspired by the symbol of red lipstick, which represents both femininity and boldness. “Men dominated church leadership, but women constituted most of the members and regular attendees and did most of what was called church work. Women gave and raised money, taught Sunday school, ran women’s auxiliaries, welcomed visitors, and led social welfare programs for the needy, sick, and elderly. They were also prominent in domestic and foreign missionary activities. One grateful minister consistently offered “great praise” to the church sisters for all their hard work” (White, Bay & Martin, 2021). Benbow asks herself the question,“What is owed to black women for that level of religiosity, what is owed to black women for that level of commitment?” where she answers, “Red Lip Theology was and is my way of trying to make sense of that.”

Red Lip Theology is a call to action for Black women to use their voices and take up space in their religion and culture. The name “Red Lip Theology” Is inspired by the symbol of red lipstick, which represents both femininity and boldness. “Men dominated church leadership, but women constituted most of the members and regular attendees and did most of what was called church work. Women gave and raised money, taught Sunday school, ran women’s auxiliaries, welcomed visitors, and led social welfare programs for the needy, sick, and elderly. They were also prominent in domestic and foreign missionary activities. One grateful minister consistently offered “great praise” to the church sisters for all their hard work” (White, Bay & Martin, 2021). Benbow asks herself the question,“What is owed to black women for that level of religiosity, what is owed to black women for that level of commitment?” where she answers, “Red Lip Theology was and is my way of trying to make sense of that.”

“Something is fundamentally broken with our faith systems, and it requires us to think critically about the world that we are in, and the world that we want to see.” (Benbow, 2023). The faith systems in many societies have been broken for black women due to the pervasive and intersecting oppressions of racism, sexism and classism. Black women’s experiences with faith are often shaped by historical traumas and systemic injustices that have impacted their lives for centuries. Within many faith systems, patriarchal norms and practices have led to the exclusion and marginalization of black women. Many religious institutions have failed to recognize or address the unique experience of black women, leading to a feeling of invisibility and erasure. “Christian nationalism is white supremacy.” (Benbow, 2023). White supremacy is an ideology that has influenced many aspects of society, including religious institutions. White supremacy in faith comes in different forms, including the privileging of white voices and experiences over those of people of color, the perpetuation of racist beliefs and practices, and the exclusion of people of color from leadership roles and decision making processes. White supremacy in faith can also manifest as violence against people of color, either through hate crimes committed by individuals or through institutional violence, such as the role of the Christian church in perpetuating colonialism and the slave trade. “Rooted in a belief that their duty to spread Christianity justified their actions, religious organizations did not only embrace human trafficking and the enslavement of millions of Africans—they actively participated.” (Bryan Stevenson, 2022). We have to acknowledge that the privilege that white people have had in religion have had a tremendous impact on black people, especially black women in faith. Throughout history, black women have been subjected to various forms of trauma including slavery, colonization and systemic oppression. These traumas have had a profound impact on their spiritual and emotional wellbeing and have created barriers to accessing and participating in faith communities. Black women are often disproportionately affected by poverty and other forms of economic inequality. This can create barriers to accessing faith-based resources and support, as many religious institutions require financial contributions or have limited resources for marginalized communities. “Black women have been the most mistreated and scandalized in U.S. society and culture as they wrestle both individually and collectively with the triple jeopardy of racism, sexism and classism,” said Stacey Floyd-Thomas, an associate professor of ethics and society at Vanderbilt University Divinity School. “If that is the case — and I believe it is — it is no wonder that black women, due to their experience of sexism, would seek out their faith as a way of finding relief, reprieve, resolution and redemption.”

In addition to providing emotional and spiritual support, faith has also been a tool for social and political activism among Black women. Many prominent Black women throughout history, including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Fannie Lou Hamer, were deeply committed to their faith and used it as a foundation for their advocacy work. Benbow does a beautiful job of explaining what it means to be a black woman who is deeply connected to their faith, and why black women in religion should be acknowledged.

Works Cited

White, Deborah G., et al. Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents. Bedford/St. Martins, 2021.

“The Role of the Christian Church.” Equal Justice Initiative Reports, 7 Nov. 2022, eji.org/report/transatlantic-slave-trade/origins/sidebar/the-role-of-the-christian-church/.

“Candice Marie Benbow’s ‘Red Lip Theology’ Is a Love Letter to Her Mother.” Shondaland, 18 Jan. 2022, www.shondaland.com/inspire/a38773165/candice-marie-benbow-red-lip-theology/.