Kate Derham

Professor Miller

HIST-128

13 May 2022

The Zero-Sum Paradigm

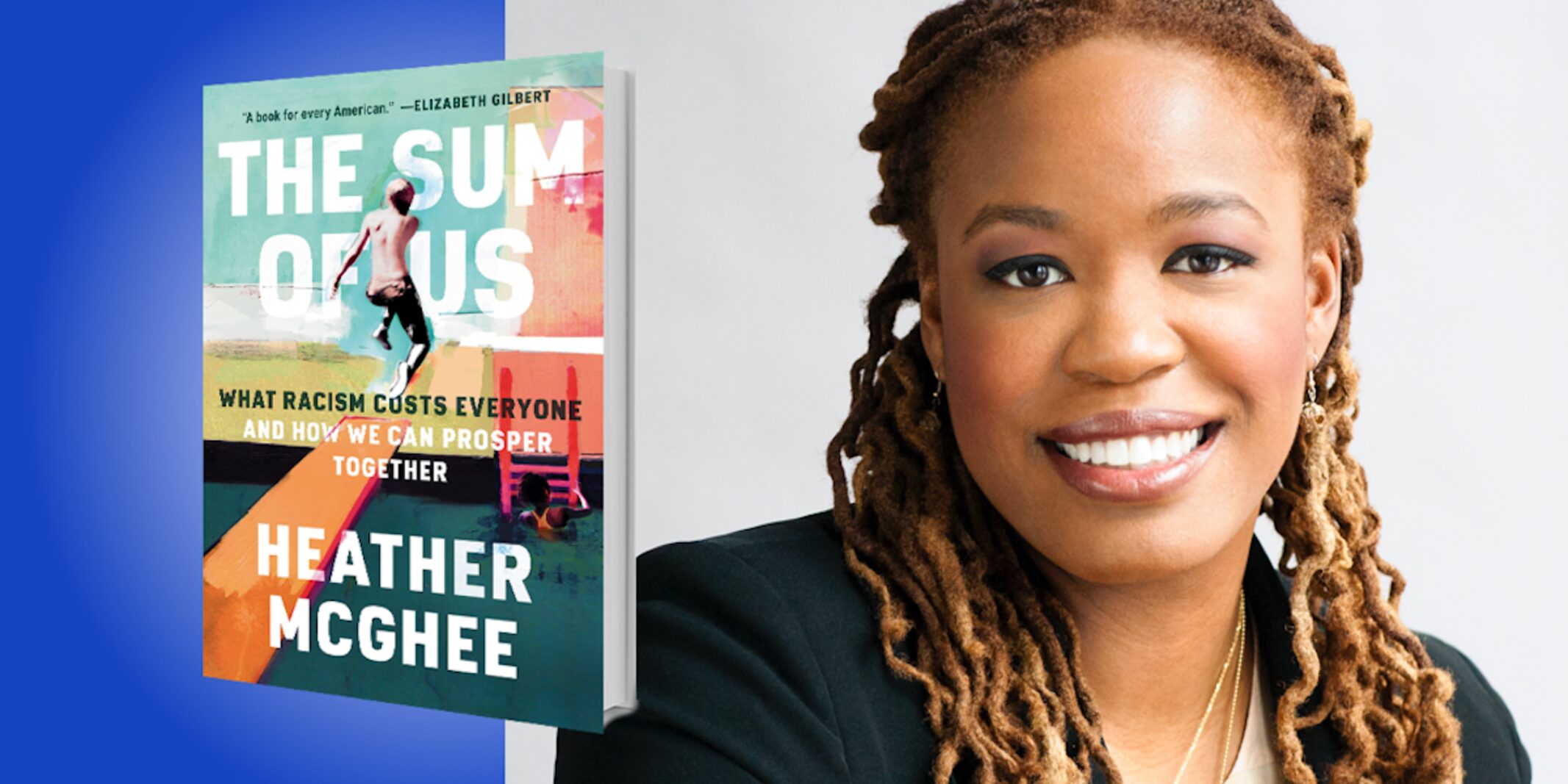

In honor of February being Black History Month, I virtually attended Heather McGee’s book talk about “The Sum of Us ”on February 28, 2022. This book talk was the fifth event for the Black History Month partnership between the San Diego Public Library and the Copley Library. Every year, these two organizations work together to bring the attendees thought provoking programs that encourage conversation and self-reflection. Heather McGee is the chair of the board for the Color of Change, the nation’s largest online racial justice organization as well as an educator. McGee explains how she wrote this book out of frustration as she mainly focuses on solutions to inequality by using data to spot problems within the American economy and its widening inequality. The predominant theme in her book is the zero-sum paradigm and how black history of racial segregation and economic inequality have an impact on society today. To deeper understand the zero-sum paradigm, an individual must explore the foundations and influences of affirmative action, housing segregation, and economic inequality in African American history and examine their lasting effects.

To introduce the zero-sum paradigm, McGee concludes that many believe in a fixed pie of well-being(zero-sum paradigm); the progress of one group must come at the expense of the other. She first saw this in a research study titled “Whites See Racism as a Zero-Sum Game That They Are Now Losing” by Michal I. Norton and Samuel R. Sommers. In their article they explain how “White Americans perceive increases in racial equality as threatening their dominant position in American society, with Whites likely to perceive that actions taken to improve the welfare of minority groups must come at their expense” (Norton & Sommers, 215). An individual may question where this deep-rooted belief of the zero-sum paradigm came from. This can be found in African American History tracing back to when affirmative action was introduced. In “Freedom on My Mind,” when discussing affirmative action, the book states that many whites believed “that affirmative action threatened their jobs and income” and Nixon supported this belief with his anti-affirmative action arguments and regimes. Many whites argued that the race and gender-based criteria for education, jobs and contracts rewarded “the dumb, lazy, and unambitious at the expense of the smart, talented, and ambitious.” White workers often quit jobs when black workers were hired, or hazed new black workers. Whites supported segregationist George Wallace or Nixon in hopes of affirmative action ceasing(Martin, Bay & White, 958). These sentiments sourced from the 1970s, directly relate to the zero-sum paradigm, as whites felt threatened by black people gaining freedom and advancements. However, this deep-rooted zero-sum sentiment began before this affirmative action era, dating back to the foundations of racial segregation and economic inequality.

Heather McGee elaborates on the zero-sum paradigm when she explains the loss of public pools in America due to residential segregation. She traveled to McHenry, Alabama and visited Oak Park. In the middle of the beautiful park was a wide flat playing field. However, she soon came to find out that there used to be a lavishly funded, resort style public swimming pool. The creation of this swimming pool was part of a “building boom” of public amenities and goods such as libraries, schools, roads, bridges, parks and pools in the 1930s and 40s. However, all of these amenities were racially segregated. There was either a white’s only sign on the pool fence or segregation was enforced through intimidation and violence at the water’s edge. Rightfully so, black families fought back and said that those were their tax dollars funding the pools and their kids should be able to swim in them. So, in response, the government drained the public pools, rather than integrate them. This didn’t just happen in the Jim Crow South, it happened in Ohio, New Jersey, California, and Washington state, where they chose to destroy a public good, rather than integrate. Aside from the usage of public amenities, the general idea of residential segregation can be seen in African American history through the use of redlining. Real estate agents used maps created by the U.S. government’s Homeowners Loan Corporation to keep African Americans corralled in the inner city. These areas were considered hazardous and designated off limits for government-guaranteed bank loans. White’s believed that providing black people with housing would bring mayhem and drive down home values, so real estate companies played on white fear and encouraged them to sell their homes at low prices, which were resold to minorities at higher prices(blockbusting)(Martin, Bay & White, 666). In Camille Zubrinsky Charles’ journal, she looks into the future effects of redlining; “living in racially segregated neighborhoods has serious implications for the present and future mobility opportunities of those who are excluded from desirable areas”(167). Heather McGee emphasized that redlining and restrictive covenants have undermined black economic advancement by preventing blacks from building up equity in their homes, limiting them from upward social mobility. Racial segregation and its detrimental effects relates to the zero-sum paradigm because at this time White’s believed that they could only be successful and have access to nice housing if the black community was neglected and segregated. Racial segregation results in income and economic inequality, which is also linked to the zero-sum paradigm.

Heather McGee touched on income inequality and the effects it had on the lives of black people in history and its continual effects. She explained that black families today earn less than 15 cents on the dollar for every dollar that the average white family has, showing that history has had an influence on this wealth and asset divide between blacks and whites. During slavery, the enslaved faced terrible hardships and worked long hours under grueling conditions. In the post-Revolutionary years, black people had restrictions on their economic lives and were confined to unskilled, menial, and low paying labor positions. The constant inequality and oppression that was present in black working and economic life was exhausting and discriminatory, so the black people called for action. In response, McGee pointed out the significance of the March on Washington. This March on Washington symbolized the civil rights movement, and the direct-action black people were seeking to end segregation in American life and achieve economic justice for black Americans (Martin, Bay & White, 865). They demanded federal job guarantees and the national living wage. However, just as the State Department was about to capitalize on their demands, a bomb exploded in Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, which had been the organizing center of the city’s civil rights demonstrations(Martin, Bay & White, 869). This response to the black community fighting for basic civil rights can also be connected to the zero-sum paradigm. White people viewed the civil rights movement as a threat and grew increasingly hostile in fear that African Americans could disempower them and threaten their positionality and access to jobs. Today, this fight for black income and economic equality is still very prevalent. Sean F. Reardon and Kendra Bischoff explain in their journal article that income inequality has “an effect that is larger for black families than for white families”(1092). They analyze modern-day effects of this; “given high levels of racial segregation in U.S. cities, the growth of income segregation among black families results in the increasing racial and socioeconomic isolation of lower-income black families in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage”( Reardon & Bischoff, 1139). Evidently, the relationship of residential and economic racism has been occurring since the 1960s and is clearly connected to the zero-sum paradigm that was and still is present in society today..

When reflecting on Heather McGee’s book talk on “The Sum of Us”, the predominant theme that is explored is the zero-sum paradigm. The zero-sum paradigm is significant to an individual’s understanding of African American History because specific concepts such as affirmative action, housing segregation and economic inequality were influenced by this paradigm and it continues to have an influence on the functionality of our society today. The continuation of structural racism in our society calls for action beginning with the acknowledgment of African American history and the influence of the zero sum paradigm.

Works Cited

Charles, Camille Zubrinsky. “The Dynamics of Racial Residential Segregation.” Annual Review

of Sociology, vol. 29, no. 1, Aug. 2003, pp. 167–207,

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100002.

Deborah Gray White, et al. Freedom on My Mind : A History of African Americans, with

Documents. Volume 2 since 1865. Boston New York Bedford/St. Martins, 2017.

Norton, Michael I., and Samuel R. Sommers. “Whites See Racism as a Zero-Sum Game That

They Are Now Losing.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 6, no. 3, May 2011,

10. 215–18, https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406922.

Reardon, Sean F., and Kendra Bischoff. “Income Inequality and Income Segregation.” American

Journal of Sociology, vol. 116, no. 4, Jan. 2011, pp. 1092–153,

https://doi.org/10.1086/657114.