More than 10,000 individuals have been recognized as saints by the Catholic Church (Petruzzello). Not a single one of these individuals, however, are of African descent. The event, “Black Saints in Waiting,” was held on February 22, 2022 in the Ministry Center at the University of San Diego, and aimed to educate its audience on this glaring issue. Speaker Reverend Kenneth Hamilton presented on the six current African-American candidates for sainthood in the Catholic Church, with an emphasis on the lack of diversity amongst prior inductees. Rev. Hamilton earned his Ph.D. in the History of Religions and Cultures, and currently serves as a pastor at St. Columba Church in Oakland, California (“Rev. Ken Hamilton, SVD, Ph.D.”). At this event, his focus was on addressing the uniformity of canonization candidates in the past, and pondering how to proceed in a more inclusive manner. The purpose of this event was to present the canonization process of the Catholic Church in a critical light, in certain regards to the following current candidates:

Pierre Toussaint

Henriette Delille

Augustus Tolten

Mary Elizabeth Lange

Julia Greeley

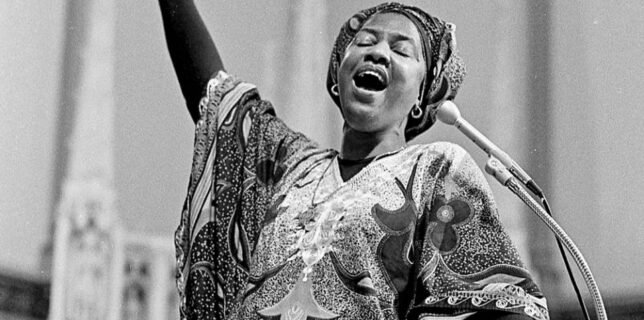

Thea Bowman

The recognition of these individuals for their efforts would be a significant step in the right direction towards the representation of African-Americans, not only of their religious contributions, but of their additions to American society throughout history. The “Black Saints in Waiting” event emphasized the importance of Black canonization in the Catholic Church for a multitude of reasons, which include but are not limited to, the religious representation of Black individuals, the recognition of their predecessors, and the reformation of the racist ideologies seemingly supported by these spaces.

Canonization of Black individuals is unheard of in the Catholic Church, meaning that the African-American Catholic community is yet to be represented by their own sainthood. Black individuals have continually been underrepresented in the Catholic community because of the unequal treatment they experienced in the presence of colonists and other white contributors. White individuals viewed themselves as superior to minority cultures, and this discriminatory ideology delayed the acceptance of African-Americans into the previously existing colonists’ church. A significant number of individuals converted to Christianity in order to escape enslavement, but baptism did not always ensure Black people freedom. As specified in Freedom on My Mind, “Virginia, one of the first colonies to codify slavery, led the way by passing laws determining how slavery would pass from parent to child and establishing that enslaved Africans who converted to Christianity would not be entitled to the same freedoms as other Christians” (White et al. 198). African-Americans have long been denied the rights and respect they deserve, as well as representation of the communities they exist in. As a result of their dissatisfactions and desires, they were able to develop a religion through which they are able to represent themselves.

Afro-Christianity developed as an extension of African traditions due to white society’s suppression of Black religions. Enslaved individuals were forced to resort to “invisible institutions” in order to preserve their practices of faith. Although African-Americans understood and embraced the fundamental aspects of Christianity, they were opposed to the idea of supporting a “white man’s religion.” Afro-Christianity allowed them to insert their own elements of African practices, such as the ring shout or slave spirituals. Since African-American individuals have not been respected by white people in the past, they are not represented by their peers presently in the Catholic community. If individuals feel wrongly or underrepresented in their religious community and by their saints, they will not feel included enough to worship freely. Afro-Christianity was created because Black people did not feel represented by mainstream religion, and they will continue to create their own churches and other spaces of worship until the Church is able to proactively recognize minority individuals.

These select individuals deserve to be officially canonized for their contributions, not only to the Catholic community, but to African-American history at large. By recognizing them with the esteemed accomplishment of sainthood, we will be able to forever remember them with the respect they deserve. As Rev. Hamilton noted, each of these candidates are being considered for Catholic sainthood because their histories are “stories [that] combine colonization with canonization.” For example, Julia Greeley, an African-American woman born into slavery, was a victim of violence at an early age. A slaveholder, in the process of beating her mother, struck Greeley’s right eye with his whip, causing her to lose sight permanently in one eye. Nevertheless, Greeley persevered in the face of adversity, and grew up to touch the lives of many. She volunteered her own resources in order to provide assistance for the less fortunate in the ways of food, fuel, or even clothing. Many of her acts of kindness were executed in the midst of the night, in order to avoid embarrassing those she aimed to assist, and she accomplished all her charitable acts on foot despite suffering acute arthritis. One of her most notable acts occurred towards the end of her life, when “she heard that the body of an elderly African-American man was going to be buried in a pauper’s grave; at [her] insistence, the man was laid to rest in the plot she had purchased for herself” (Hardaway 11). Shortly after, in June of 1918, Julia Greeley passed away – without a burial plot. In a generous act of benevolence, Greeley sacrificed her own resting place for another in need. She is often referred to as “Denver’s Angel of Charity,” but she deserves to be recognized officially for the contributions she has made to the community. A strong case could be made for her canonization, supported by the tireless efforts she spent helping others.

Julia Greeley is one of only six Black candidates for canonization, all of whom are vying to be the first African-American saint amidst a sea of white faces. The decision to canonize an African-American as a saint in the Catholic Church is also the decision to recognize the racism that has been ever so prominent in the past. The development of space and room for this recognition to occur is vital to not only the promotion of diversity, but of equity as well. The canonization of Black Catholic saints will mean nothing if African-Americans continue to be denied the equal opportunities and fair treatment they’ve been previously denied. Official recognition of any of these figures goes hand in hand with beginning to recognize the racist practices demonstrated by the developments of the Catholic Church.

The respectful representation and recognition of Black contributions will hopefully encourage a reformation of the racist ideologies that have existed historically. Although the Catholic Church has been established for over 2,000 years without signs of improvement in its policies (Stanford), it can never be too late to make a difference. The determination of the African-American community models an important lesson: unified resistance remains a critical strategy of reform. The results of their efforts are evident throughout history, especially following events such as the March on Washington Movement during World War II. Organized by A. Philip Randolph in January of 1941, this demonstration invited Black Americans to the nation’s capital in order to “demand equal opportunity for blacks in defense industries and an end to their ‘humiliation in the armed services’” (White et al. 766). Randolph held firmly to his demands, eventually pressuring President Roosevelt enough to issue Executive Order 8802, which banned practices of racial discrimination in defense industries and created the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). This outcome was a small step in the right direction, alluding to the importance of resistance in African-American advocacy for their rights.

The reformation which Black people have consistently had to advocate for is alarming on many fronts. However, their strategies of resistance have proven to be effective in attaining their goals, as seen in the March on Washington Movement. By clinging firmly to their demands, African-Americans have made significant change throughout history, and this technique might also be effective in promoting the canonization of the proposed candidates. By canonizing those of African descent who deserve to be recognized, we can begin to reform unjust practices alongside one another. One of the candidates, Thea Bowman, depicted her hopes for the future ever so elegantly in her journal article, “Black History and Culture”:

When we as delegates to the National Black Catholic Congress live and celebrate our history and our culture, we will address concerns that many Black Catholics express and that are reflected in the working documents of this National Black Catholic Congress. When we understand our history and culture, then we can develop the ritual, the music, and the devotional expression that satisfy us in Church. We can develop the cognitive based religious education and the catechis that will speak to the hearts of our people. We can develop the systems of service that respect us, who we are, how we operate as a people, and how our families really are. (Bowman 310)

In this literary work, Bowman indicates a desire to address the concerns held by Black people regarding the Church. More importantly, however, she acknowledges that not all African-Americans are satisfied by the Catholic practices. This is true, especially after the development of Afro-Christianity. Yet, Black individuals still deserve to be treated with respect and accepted into the community with open arms. Institutional racism cannot be resolved overnight, but canonizing these deserving candidates would be significant progress towards remediation and reform.

At the “Black Saints in Waiting” event, Rev. Hamilton reminded his audience that the representation and recognition of Black people in the Catholic Church is critical to the reformation of the institution’s current ideologies. The stories of these candidates embody not only Black cultural practices, but African-American history as well. If these individuals are canonized, they will leave an important legacy, one that opens a door for future generations to lead the way in making a difference for Black people and their honorable history.

Works Cited

Bowman, Thea. “Black History and Culture.” U.S. Catholic Historian, vol. 7, no. 2/3, 1988, pp. 307–10, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25153836. Accessed 5 May 2022.

Hardaway, Roger D. “African-American Women on the Western Frontier.” Negro History Bulletin, vol. 60, no. 1, 1997, pp. 8–13, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24766796. Accessed 4 May 2022.

Lambert, Aaron. “Denver’s ‘Angel of Charity’ On Road to Sainthood.” Denver Catholic, Archdiocese of Denver, 31 Aug. 2021, https://denvercatholic.org/denvers-angel-charity-road-sainthood/.

Petruzzello, Melissa. “Roman Catholic Saints.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/story/roman-catholic-saints-hallowed-from-the-other-side.

“Rev. Ken Hamilton, SVD, Ph.D..” NBCCC, https://nbccc.cc/rev-ken-hamilton-svd-ph-d/.

Stanford, Peter. “Roman Catholic Church.” BBC, BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/catholic/catholic_1.shtml.

“The First African American Coloradoan to Be Nominated for Sainthood.” Denver Public Library History, 23 Dec. 2021, https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/first-colorado-saint.

White, Deborah Gray, et al. Freedom on My Mind. 3rd ed., BibliU version, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2020.