In the trans-Atlantic slave trade, millions of Africans were stolen from their homes, crammed into ships, and sold into slavery. From the moment they were captured, the life of enslaved Africans were filled with more violence than most modern-day Americans can fathom. Reading facts and figures is important to learn history, but it doesn’t help conceptualize the suffering that was a reality for thousands. While reading first hand accounts and watching fictionalized re-creations of the Middle Passage helped provide a picture in my mind (and certainly made me sick to my stomach), I still felt disconnected from the narratives provided. It wasn’t until I attended the first part of USC Thorton’s “From Tragedy to Triumph,” that I found a way to truly connect to the horrors of the middle passage. Art transcends the boundaries of what the brain is able to imagine and allows you to connect directly to the emotions, fostering a deeper connection than other mediums.

The middle passage was the third leg of the triangle trade–cash crops were exchanged for European goods, European goods were exchanged for so-called “human cargo,” and these enslaved Africans were exchanged for cash crops. From readings in our textbook, I understood that not only was unnecessary violence rampant, but Africans were packed like sardines in the ship’s hold.

The inclusion of first-hand accounts illustrated the horrors in more detail. For example, in a passage of The Interest Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, the eleven year old boy explains that he “now wished for the last friend, Death, to relieve me.” It’s impossible to read this without feeling sympathetic for Olaudah Equiano, but feeling sympathetic and being able to empathize with Equiano’s experience are two completely different experiences.

Even after reading personal accounts and watching a recreation of the middle passage in Roots, it was still hard to conceptualize. The horrors of the middle passage were too great; it seemed impossible that I could have any grasp on what it would be like to live through. Through the video USC presented, I was able to connect to the emotional experience of those impacted which improved my understanding.

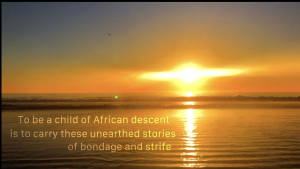

The student-made video shown in the program acknowledged both the experience of the viewer and told the history of the middle passage through music, dance, poetry, and imagery. It began, “Let me tell you a story of the men and women whose blood still runs in the ocean I swim in.” This line is representative of the language throughout–metaphorical and educational all at once. As well as the focus on the middle passage, the presentation discussed modern day issues, such as unlearning inaccurate versions of history and how slavery still exists in different ways.

When the voice-over illustrated the choice that Africans faced between the unknown and plunging to their death in the sea, a Sinte performer on the beach danced. The rhythmic dance is traditional to west Africa, meant to celebrate the water. As well as providing beautiful background visuals and music, it emphasizes how the ocean should be something that is appreciated–not a reminder of a forceful migration and the resting place of untold thousands.

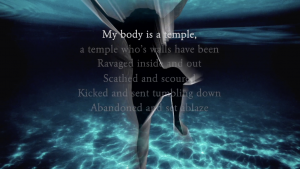

One particular moment that felt different than anything I had ever seen before was a poem by Awo Jama. Before showing the video, students discussed how they looked at pieces of writing from Black creators and first hand accounts of the middle passage. Jama’s poem–which repeated the phrase “My body is a temple,” before detailing how the temple was abandoned and ultimately had been destroyed–was so beautiful I thought it was a published piece of poetry.

Below you can see both my favorite stanza and, coincidentally, my favorite visual. The silhouette of the woman sunk as different stanzas appeared and this stanza just so happened to be the one where she was perfectly centered. I also managed to screenshot just as the lines of the poem began to fade, which perfectly encapsulates how “My body is a temple,” as the most hopeful line, is the most important.

My interpretation of the poem was that this was an enslaved woman speaking and the verb “ravaged” leads me to believe she has been raped as well as mistreated in other violent ways, as was unfortunately all too common for enslaved people. I thought the emphasis on the body as a temple–despite the disrespect that has been done to it–was beautiful. Often the spirituals that Africans would sing as they worked on plantations would focus only on religion, because as enslaved people they had no control over their bodies so their only source of hope was spiritual salvation, not existential. In this poem, the woman knows her body deserves respect, even if it receives none.

I was surprised by how touched I felt by the poetry throughout the video. Many times I find poetry to be too abstract or too dramatic, but in this case I felt that the reading of the words, the music, and imagery combined to portray the pain and suffering in a way that facts alone could not.

The video also touched on what Christina Sharpe would call “Living in the Wake.” Although slavery was outlawed in 1865, it’s effects have not gone away. Every person has to reckon with the horrors of history. Even just living is a resistance for Black people because for so long white people tried to strip away Black rights, tried to reduce them to a separate group that didn’t deserve to live. Many Black people today can’t trace their roots back as far as the middle passage, but even if they can identify when their family came to America, they likely don’t know where they came from. White people stripped thousands of Black people from their homes and their cultures and this still affects them today. African Americans have to carry the knowledge that their ancestors suffered and that their white peers benefit from the suffering of their ancestors.

There may be no way to truly understand what African people went through at the hands of slave-traders and slaveholders. But art speaks to our emotions, something that are universal regardless of our life experiences. No matter the cause, sadness or anger are the same for everyone, giving us a way to connect. By creating a video that invoked such strong emotions and demonstrated the complex and lasting effects of the middle passage, the USC Thorton students provided a window that anyone could look through to better connect to history.

Works Cited

White, Deborah G., et al. Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents. Bedford/St. Martins, 2021.

Sharpe, Christina Elizabeth. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, 2016.