If one neighborhood shows how discriminatory housing practices first came to play in San Diego, it would be Logan Heights. However, Logan Heights is also a primary example of how African Americans took a situation in which they were alienated from others and denied basic rights unjustly, yet created community and goals among themselves. These forms included family life, spiritual and church life, and education. Eventually, African Americans demonstrated their self-reliance and determination. Although still heavily discriminated against, some were able to rise up and become socially prominent, such as Issac Wooden.[1]

Many factors led to Logan Heights becoming the first African American neighborhood in San Diego. In 1852, a San Diego Grand Jury demanded that “these colored men be compelled to leave our town.” [2] The African American presence in San Diego clearly was not welcomed. However, Logan Heights became the one location that they were allowed to live. During World War II, the number of African Americans increased, but not because they felt more welcome. The increase came from a new need for people to fill in industrial jobs. During this time, African Americans encountered multiple barriers when trying to find a place to live in San Diego. Although President Roosevelt executive order banned discrimination in workplaces and in the war industry, it was not until the war had ended that more focus was given to the discrimination in housing.

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act “prohibited discrimination by direct providers of housing” based on religion, national origin, color, and race.[3] Yet, this did little to change San Diego’s perspective. A study done by Leroy Harris showed that “restrictive covenants in real estate deeds and the role of real estate agents in the formation of segregated housing patterns were a very strong force in creating a segregated San Diego.”2 Frank Norris also acknowledges the fact that the concentration of African Americans in the area could have been due to many factors, but largely white flight and the increased ability for white people to move to suburban regions as well as the racially discriminatory housing contracts.[4] Realtors themselves with their own prejudices would prevent African Americans from buying houses in predominantly white areas, even if they could afford it. One sign in La Jolla read, “No part of said property, or any buildings thereon, shall be used or occupied by any person not belonging to the Caucasian race, either as owner, lessee, licensee, tenant, or in any other capacity than that of servant or employee.” However, San Diego as a whole worked to prevent the African American presence from spreading. The Rumford Act was passed in 1963 by the California Legislature and strove to end discrimination at the hands of landlords. In 1964, The San Diego Realty Board fiercely endeavored to annul the Rumford Act through ballot proposition. By 1965, the Fair Employment Practices Commission labeled it “one of the most segregated areas in the country.”2 The continual discrimination against African Americans who were trying to find a place to live led Logan Heights to become “a center for black populations.” 4

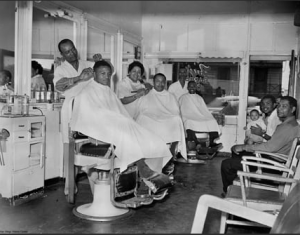

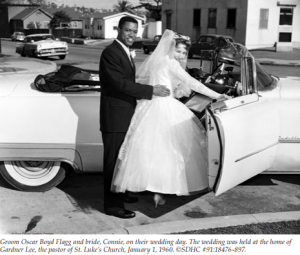

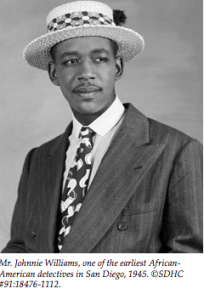

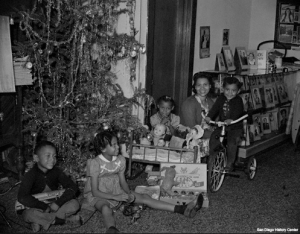

Norman Baynard, who lived in Logan Heights, photographed the everyday lives of African Americans in the neighborhood from 1939-1986. His collection of photographs truly shows the inner workings and progression of the community. His pictures document the rise and existence of black businesses, spaces, and organizations such as women’s hair salons, barber shops such as Fay’s Barber Shop, political entities, and events that were centrifugal to African American culture. Sunday Mass, baptisms, and graduation, and marriage were all events that gained much attention in the neighborhood.[5] They saw graduation as social advancement and the accomplishment brought much pride in the community. Sunday service was a time for the community to gather and connect spiritually and socially. The development of several chuches enticed an even greater amount of African Americans to move to Logan Heights.4 Originally, families that moved to Logan Heights were mostly middle-class or upper middle-class African Americans. As time progressed, a small number of families rose in social and economic status, and began to branch out of southeast San Diego.

One interview of Jewel Hooper focuses upon her journey and how she came to move to Logan Heights. Before she moved from Washington, D.C., she was told that with money, she could move anyplace that she wished in San Diego. She says, “That was the biggest lie that was ever told.” After encountering the reality of San Diego, she states, “We knew where we could live and where we shouldn’t even try. We couldn’t try north of Market, and for a long time east of 47th Street.”[6] In 1964, she attempted to buy a house, and although she had the money to do so, she was denied. She then moved to Logan Heights. Now at 91 years old, she sees the outflux of African Americans from Logan Heights as a sign of progression in working against what the racially discriminatory housing practices once established and believes that “They left because they could.”6 This can be seen in the fact that the Logan Heights African American population has decreased to only 7% as of 2010. [7] The blossoming and growth of black community and culture made this movement possible. The communities and churches “engineered cultural and social capital and their belief in God engineered religious capital, all of which made significant contributions to these Black [male] students’ academic achievement.” [8] The culture and goals developed catapulted the younger generation into accomplishments such as graduation. This led to the pursuing of even higher education, and then employment. With the social rise that came through the cultivation of values within the community, African Americans freed themselves from Logan Heights.

The outflux of African Americans in Logan Heights stands as a testament of the power and persistence of black culture. The strength with which the culture was so deeply rooted made it the perfect agent of advancement. The power of black culture in Logan Heights was held in its capacity to propel. Logan Heights serves as a historic symbol of how African Americans coming to San Diego suffered under the racially discriminatory housing practices and were forced to live in a non-desirable place, yet made it their own community. The fostering of their own traditions, cultures, and goals helped them thrive and eventually led to them moving past what held them back before.

[1] Gail Madyun and Larry Malone, “Black Pioneers in San Diego 1880 – 1920,” San Diego History Center, Accessed April 23, 2019, https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1981/april/blacks/.

[2] Jim Miller, “San Diego’s Racial Unconscious: History Is the Narrative That Hurts,” San Diego Free Press, Accessed April 23, 2019. https://sandiegofreepress.org/2015/02/san-diegos-racial-unconscious-history-is-the-narrative-that-hurts/#.XL6eIc9KjUo

[3] “The Fair Housing Act.” The United States Department of Justice. December 21, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://www.justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-1.

[4] Frank Norris, “Logan Heights,” The Journal of San Diego History, 1983.

[5] Norman Baynard, “Norman Baynard Collection,” San Diego History Center : Online Collections, Accessed April 11, 2019. https://sandiegohistory.pastperfectonline.com/bycreator?keyword=Baynard, Norman (1908-1986).

[6]Adrian Florido, “How Segregation Defined San Diego’s Neighborhoods,” Voice of San Diego, March 21, 2011.

[7] “Demographic and Socioeconomic Profile 2010.” 2016.

[8] Cheron Byfield, “The Impact of Religion on the Educational Achievement of Black Boys: a UK and USA study,” British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2008.

Clients getting their hair cut at Fay’s Barber Shop- a black-owned shop in Logan Heights

Baptism at an unknown church in Logan Heights

Marriage was largely celebrated because family acted as a cornerstone of values.

Norman Baynard photographed many “firsts,” such as this picture of Mr. Johnnie Williams.

The Baynard family celebrating Christmas in Logan Heights.

An unnamed school group in Logan Heights