Black history is composed of many years of culture, oppression, discrimination, resistance, and a fight for equality. Particularly in the era following the Civil War, we saw the rise of intense discrimination in response to the outlawing of slavery. The Jim Crow period was characterized by the key doctrine put forth by the historic court case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which was the idea of “separate but equal.” As many of us know by now, however, this period embodied anything but equality. There were many central people, movements, places, etc. that represented and championed an embrace of black culture, even when society was trying to diminish it. Focusing in on San Diego, one of these key places was the Douglas Hotel, also known as the “Harlem of the West.”

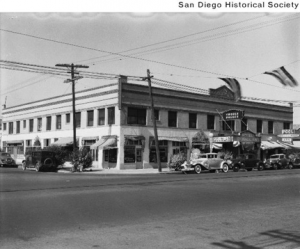

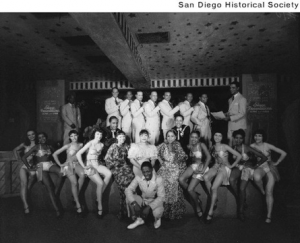

African American businessman George Ramsey and Robert Rowe built the Douglas Hotel in 1924 in order to provide African Americans a place of quality lodging, something that was missing during this intense time of segregation. The two owners sought a name that would empower African Americans and embody black culture. They selected the name “Douglas” after Frederick Douglas, a former slave and a key activist in the African American community. The two-story structure was composed of 45 hotel rooms, a restaurant, a bar, and a decadent ballroom. This ballroom also served as the hotel’s nightclub, which became known as the Creole Palace. The term, “creole,” holds its own significance to African American culture. Though at its conception it referred to those of mixed African and European decent, it has come to represent more. It exceeds racial boundaries in that it emulates its own culture based on blended and mixed heritages. Though it is not concretely known why the name Creole Palace was selected, it likely had to do with the fact that creole is a vast celebration of culture in general, despite race or ethnicity.[1]The rise of jazz music in the 1920s contributed to the success of the club, and it went on to host celebrities such as Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Count Basie. The Creole Palace became the element that the hotel was most known for.[2]The building itself was simple; a plain white structure with overhangs on the first-floor windows, one large overhang reading “The Douglas Hotel,” and a large, light up marque marking the place of the Creole Palace.[3]The historic building served as a cultural hub for African Americans in California. Because it gained popularity at the same time that Harlem was becoming a black cultural center in New York, it was given the nickname “The Harlem of the West.” Though a seemingly celebratory venue, the hotel did bring about some complications. The raciness of the club in addition to the consumption of alcohol during the period prohibition brought about controversy. This controversy, however, was what helped make this establishment so memorable, as it provided a positive nightlife experience to people of all races. The hotel operated for over 30 years until it was sold by George Ramsey in 1956 and was demolished in 1985. Today, a plaque reminds onlookers of the historical site that was once located on Market Street in the Gaslamp District of San Diego.[4]

The Douglas Hotel was and continues to be a place of prominence for the African American community. According to the Centre City Development Corporation of San Diego, “It is clear that the Douglas Hotel was more than a hotel and nightclub and that George A. Ramsey was more than a businessman and club owner. Besides offering employment to large numbers of Black performers, service staff, shop workers, and others, the Douglas Hotel and Mr. Ramsey stood out as an example of Black success.”[5]The 1900s were a time of vast resistance towards the black community, not just in the south, but also in states such as California. In San Diego, there was the particular issue of redlining, which caused separation and hostility in terms of areas of residence. This was made possible by private funds as well as mortgage agreements imposed by the government.[6]Despite its central mission of providing residence to African Americans in the city, an important aspect to note and perhaps one of the most significant facts of the hotel is that it was open to all, no matter what race. In fact, George Ramsey put out an advertisement in the August 1935 issue of the Chula Vista Star, stating that “Everyone is welcome” to both the Creole Palace and the Douglas Hotel. In doing so, Ramsey promoted quality by way of community building. This sense of coming together served as its own form of resistance to segregation, though it was not considered direct action. Putting up as strong front and building relationships with fellow African Americans and whites alike kicked against societal confines imposed due to race. In this same ad, he thanks the citizens of San Diego and Chula Vista for bringing “Harlem to the West” by contributing to and supporting the hotel as a place of cultural celebration.[7]This hotel brought a change to the social dynamic of San Diego by not only providing lodging but also bringing a buzzing nightlife full of jazz music and inclusivity for the African American community. Its performers were also representative of both genders, having male and female actors, dancers, and singers.[8]This inclusivity of genders and races, in addition to the hotel’s central mission make it a venue of historical and cultural importance to San Diego.

The Douglas Hotel provided a place of quality lodging and bursting nightlife during a period of intense segregation and discrimination in the United States. The lack of equality at this time inspired George Ramsey and Robert Rowe to construct this historic building. They championed the idea of inclusion and community, encouraging those of all races and genders to partake in all that the Douglas and the Creole Palace had to offer. The “Harlem of the West” celebrated black culture, despite society’s resistance, by providing jazz music to its audiences, providing employment to African Americans in San Diego, and providing a welcoming environment. The plaque that remains in the hotel’s place reminds us today that black history is prevalent and integral to our nation’s history as a whole and that the struggle and adversity faced by this group did not stop them for fighting for equality.

Bibliography

Carrico, Richard L., Stacie Wilson, Stacey Jordan, Ph.D., and Jose Bodipo-Memba. Centre City

Development Corporation Downtown San Diego: African American Heritage Study.

PDF. San Diego: Centre City Development Corporation, December 2004.

Cavanaugh, Maureen, et al. “Redlining’s Mark On San Diego Persists 50 Years After Housing

Protections.” KPBS Public Media, 5 Apr. 2018, www.kpbs.org/news/2018/apr/05/Redlinings-Mark-On-San-Diego-Persists/.

“Creole History and Culture.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 9 Jan.

2018, www.nps.gov/cari/learn/historyculture/creole-history-and-culture.htm.

“Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (Black Americans).” National Parks

Service. November 17, 2004. Accessed April 11, 2019.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/5views/5views2h37.htm.

George J. Ramsey. “Harlem to San Diego.” Advertisement. Chula Vista Star, August 30, 1935,

5.

Sidney, Guy. Exterior of the Creole Palace at the Douglas Hotel. 1932. California Border

Region Digitization Project, San Diego.

Sidney, Guy. Group Portrait of Creole Palace Performers. 1935. California Border

Region Digitization Project, San Diego.

[1]“Creole History and Culture.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 9 Jan. 2018, www.nps.gov/cari/learn/historyculture/creole-history-and-culture.htm.

[2]“Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (Black Americans).” National Parks

Service. November 17, 2004. Accessed April 11, 2019.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/5views/5views2h37.htm.

[3]Sidney, Guy. Exterior of the Creole Palace at the Douglas Hotel. 1932. California Border

Region Digitization Project, San Diego.

[4]“Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (Black Americans).” National Parks

Service. November 17, 2004. Accessed April 11, 2019.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/5views/5views2h37.htm.

[5]Carrico, Richard L., Stacie Wilson, Stacey Jordan, Ph.D., and Jose Bodipo-Memba. Centre City

Development Corporation Downtown San Diego: African American Heritage Study.

PDF. San Diego: Centre City Development Corporation, December 2004.

[6]Cavanaugh, Maureen, et al. “Redlining’s Mark On San Diego Persists 50 Years After Housing Protections.” KPBS Public Media, 5 Apr. 2018, www.kpbs.org/news/2018/apr/05/Redlinings-Mark-On-San-Diego-Persists/.

[7]George J. Ramsey. “Harlem to San Diego.” Advertisement. Chula Vista Star, August 30, 1935,

5.

[8]Sidney, Guy. Group Portrait of Creole Palace Performers. 1935. California Border

Region Digitization Project, San Diego.