USD MAG

Summer 2023

ON A ROLL — LIVING LIFE IN FULL COLOR

Celebrating the renaissance of some of USD’s most resilient students.

Summer 2023

Celebrating the renaissance of some of USD’s most resilient students.

Summer is a time for fun, family, vacations and so much more. For some, it means lazy days at the beach, a cross-country road trip or perhaps a camping excursion in the mountains. For many USD faculty members, the summer months are spent delving into research while making plans for an enlightening fall semester. At the same time, USD students hit the trail to help with facultyled research projects or head to the office to work with alumni as part of an internship or a summer job, while still others take advantage of the opportunity to study abroad.

If you are focused on the vacation component of summer, we have you covered. Our Traveling Toreros program provides fantastic opportunities for adventures with like-minded travelers during summer and beyond. From spiritual journeys such as walking the Camino de Santiago to exotic Tahitian cruises, we have the perfect itinerary planned for you. And who better to hang out with than your USD family?

For many alumni, parents, and incoming first-year students, this time of year means attending one of more than 20 Summer Send-Offs held around the country. Coordinated by Renda Quinn ’86 and the Office of Parent and Family Relations, these events provide the opportunity for incoming students to meet others from their area, learn more about what to expect at USD, and get answers to all their questions as they start on their path to becoming Toreros for life.

A number of those incoming students are part of a unique constituency — legacies. Family legacies have been an important part of the university for nearly our entire existence. As we approach our 75th anniversary, we can look back to find names that represent multiple generations of Toreros — names such as Stehly, Chucri, Alessio, Partynski and many more. For the fall of 2023, approximately 10% of our first-year class is made up of students who have another Torero in their family.

We are grateful for those strong connections within the Alumni Association, which continues to flourish and grow with and in support of the university. With more than 77,000 alumni living in San Diego and around the world, our staff and volunteers strive to live out our mission, which is to engage and enrich the Torero community for life.

Among those volunters, it is with sincere gratitude that we thank Vince Moiso ’95, whose term as president of the Alumni Association Board of Directors is expiring on June 30. Like many others, his is a family of multiple Toreros. Daughter Viviana will graduate in 2024, joining Vince and his wife, Shelby DePriest Moiso ’94, as USD alumni.

Vince’s tenure was marked by a commitment to strategic planning, including representing alumni on USD’s strategic planning task force. He also led the USD Alumni Association to further enhance strategic task forces based on four pillars of engagement — Communication, Experience, Philanthropy and Volunteerism. A Diversity,

Equity, and Inclusion Task Force also was formed during this time and has been incredibly active. We thank Vince and know that the Moiso family will remain very involved!

Taking over the helm in a twoyear term is Helen Kasperick Finneran, a member of the Class of 1981. She is part of a large Torero family herself. She and her husband, John Finneran III ’80, are parents of Dr. John Finneran IV ’08. In addition, five of Helen’s six siblings followed in her footsteps to Alcalá Park. She and her husband both retired after spending their entire careers with Lockheed Martin and now reside in Carlsbad. They have both been active USD volunteers for many years, supporting University Ministry, the Torero Football Club, and other USD projects. We’re excited to have Helen leading

the Alumni Association during a critical moment in USD’s history. I’ll end with a quick note of thanks to Julene Snyder, who helped make USD Magazine what it is today.

To all our alumni, parents, colleagues and friends, enjoy the summer. And enjoy being a part of this wonderful university. We hope you’ll join us at one of our many USD Alumni Association events around the country and throughout the world. Network with your fellow alumni. Hire a graduating senior or a fellow alumnus or alumna. And take time to visit our beautiful campus, perhaps for Homecoming and Family Weekend. It’s always a great day to be a Torero!

Charles Bass Senior Director of Alumni Relations In Torero Spirit,[president]

James T. Harris III, DEd

[vice president, university advancement]

Richard P. Virgin

[associate vice president for university marketing and communications, university advancement]

Russell J. Yost ryost@sandiego.edu

[editor/senior director]

Julene Snyder

[senior creative director]

Barbara Ferguson barbaraf@sandiego.edu

[editorial advisory board]

Charles Bass

Sandie Ciallella ’87 (JD)

Minh-Ha Hoang ’96 (BBA), ’01 (MA)

Lynn Hijar Hoffman ’98 (BBA), ’06 (MS), ’18 (MS)

Michael Lovette-Colyer ’13 (PhD)

Kristin Scialabba ’21 (PhD)

Rich Yousko ’87 (BBA)

[usd magazine]

USD Magazine is published three times a year by the University of San Diego for its alumni, parents and friends. U.S. postage paid at San Diego, CA 92110. USD phone number: (619) 260-4600.

[class notes]

Class Notes may be edited for length and clarity. Photos must be high resolution, so adjust camera settings accordingly. Engagements, pregnancies, personal email addresses and telephone numbers cannot be published.

Please note that content for USD Magazine has a long lead time. Our current publishing schedule is as follows: Class Notes received between Feb. 1–May 30 appear in the Fall edition; those received June 1–Sept. 30 appear in the Spring edition; those received between Oct. 1–Jan. 31 appear in the Summer digital-only edition.

Email Class Notes to classnotes@sandiego.edu or mail them to the address below.

[mailing address]

USD Magazine Publications

University of San Diego 5998 Alcalá Park San Diego, CA 92110

[website] www.sandiego.edu/usdmag

[be blue go green]

USD Magazine is printed with vegetable-based inks on paper certified in accordance with FSC® standards, which support environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests.

[0723/Digital/PUB-23-3619]

Leaders of Influence

Four USD leaders were recognized by the San Diego Business Journal in its 2023 list of the region’s “Top 50 Black Leaders of Influence,” celebrating individual achievements and USD’s collective effort toward equity and excellence. Honorees included: Senior Vice President and Provost Gail F. Baker, PhD; Vice President of Student Affairs Charlotte Johnson, JD; Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Regina Dixon-Reeves, PhD; and School of Leadership and Education Sciences Dean Kimberly White-Smith, EdD.

USD’s Torero Renaissance Scholars program supports students like Anita Duong ’23 (MA), who grew up as an unaccompanied minor and is now among the less than 1% of the nation’s foster youth who’ve earned a master’s degree. She’s not stopping there — and will soon pursue her PhD. The TRS program, established in 2010, provides support and resources to USD students who identify as former foster youth, who are emancipated or unaccompanied minors, who were in legal guardianships, or who are homeless or are at risk for becoming homeless.

Becoming the Mission

A team of employees were part of Leaders in Mission Formation, a new way of onboarding employees and sharing what it means to work at a Catholic university.

Jessica Garcia ’16, who’s earning a master’s in school counseling from the School of Leadership and Education Sciences, is getting hands-on experience from the guidance counselor who inspired her in high school.

In February, the campus proudly celebrated the 12 recipients of USD’s second annual Diversity and Inclusion Impact Awards, who are making a difference on campus.

The Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering is 10 years old. USD celebrated the 10th anniversary in many ways — including an event on March 28, featuring miniature drone test flights, 3D print demonstrations, a 360-degree photo booth, raffles and a ceremonial cake cutting.

The Fire Inside is Ablaze

Solymar Colling’s athleticism, fiery competitive nature and storied work ethic were the foundation for her decorated amateur tennis career — and her on-court accomplishments at USD are as impressive as they are numerous.

A Passion for Pancakes

Amory Fratoni ’15, the lead operations manager for a volunteer organization known as Pancakes Serving Up Hope, has learned that sometimes giving someone a warm meal — complete with buttery, syrupy goodness — is a way of also serving up hope to many who are homeless in San Diego.

Former running back Jonah Hodges ’16, who was named a Football Championship Subdivision Second Team AllAmerican Running Back and Male Torero Athlete of the Year in 2016, says football taught him many important lessons in life — including the importance of timing and the value of waiting and being patient as well as what means to be a USD Man, someone who has his nose to the grindstone, is a hard worker and goes the extra mile for his teammates.

Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science graduate

Anthonia “Tonia” Okoh ’17 (MSN), ’23 (DNP) was inspired to become a nurse after caring for her parents in her home country of Nigeria. When COVID-19 hit, she decided to get her doctorate and juggled her doctoral studies while working as an emergency room nurse and taking care of her three children during her husband’s deployments with the U.S. Navy.

Photo of Anita Duong ’23 (MA), by Maya (Alé) Delgado

WEBSITE: sandiego.edu/usdmag

FACEBOOK: facebook.com/usandiego

TWITTER: @uofsandiego

INSTAGRAM: @uofsandiego

E-MAIL: classnotes@sandiego.edu publications@sandiego.edu

U.S. MAIL: USD Magazine University of San Diego 5998 Alcalá Park San Diego, CA 92110-2492

[faith in action]

by Julene Snyder

This spring, a select group of 11 University of San Diego staff and administrators made up the inaugural cohort of Mission Integration’s first Leaders in Mission Formation Program. The pilot program — described as an “opportunity for critical

conversations and discernment about what it means to work at an engaged and contemporary Catholic university” — included participants from across campus and from all faith backgrounds, including those who don’t identify with a particular faith tradition.

Over time, the way new employees have been onboarded, including learning what it means to work at a Catholic university, has evolved and shifted. However, this new program is meant to provide a much deeper dive.

“When I started being a part of orientation, along with

[Director for Mission] Mark Peters and [Vice President for Mission Integration] Michael Lovette-Colyer, people started coming to me afterward asking if we could get together and talk,” recalls Director of Mission Integration and Center for Christian Spirituality Erin Bishop. “They’d have questions like, ‘Do I belong here?’ and ‘Is this the place for me?’ and ‘How do I fit in?’ ”

So, in 2022, when LovetteColyer assumed his new role, he asked Bishop to establish a formation program that would

provide a broader, deeper sense of what it meant for people to engage with USD’s mission and Catholic identity, while respecting what Bishop describes as “people’s sense of their own personal mission.”

She knew that she wanted to attract key campus leaders to the program when she began that work. “When tensions arise — when there’s a renaming of Serra Hall, when there are student groups that want to distribute condoms on campus, when there’s a war going on — how does our Catholic identity surface?” she inquires.

She sees the program as an aid for staff to stockpile the resources they may need during the course of doing their jobs. For example, for a social media manager to parse current events and how they intersect with the views of the Catholic Church.

“While we realize that we have non-Catholics working here, even the Catholics who work here may not be the most equipped or resourced or studied in that world or reality,” Bishop explains. “We settled on a more engaging process of people recognizing what gifts they bring in and how they’re already doing good work.”

The program started with a full-day retreat in January to bond as a community. Bishop says the most impactful part of that day was choosing different places on campus and asking people to reflect on their experiences of those places.

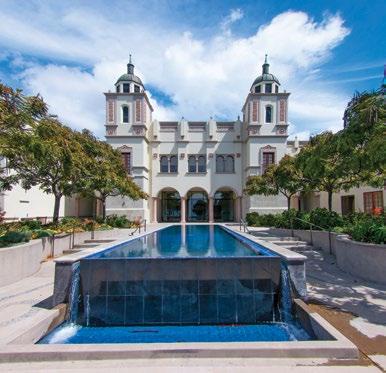

While they visited the spots one might expect — Founders Chapel and The Immaculata come to mind — they also were taken to more tucked away locations. “We sent them to The Garden of the Sea, the pillars of faith statues near the Jenny Craig Pavilion and the Learning

Commons,” Bishop explains. “We asked them to think about how these places on campus speak about the Catholicism at USD. This idea that the university has a history and a purpose can be missed day to day when we’re running from meeting to meeting. This is a way to deepen our sense of what this place is about.”

Each participant was given three questions and asked to present their reflections about their experience to the group. The program’s subsequent monthly gatherings were focused on topics such as community, faith, the Catholic Intellectual Tradition, the liberal arts and how best to confront humanity’s urgent challenges.

Participant Matthew Yepez — who came to USD in June 2022 to take the helm as senior director of the Career Development Center — found the program edifying. “I think it helps me to better align with the mission, and to help my team members. We all want to know how best to help students to launch their lives and be successful,” he says.

He was particularly struck by roaming campus during the retreat. “It was powerful to pause and reflect on the history and its intricacies,” Yepez recalls. “I had a new appreciation for how special a place this is and was impressed by the concept that our Catholic identity means this is a welcoming place, even for those of us who aren’t practicing.”

Bishop echoes that sentiment. “Learning about the history of USD doesn’t mean we haven’t evolved from 30 years ago,” she notes. “We want people to think about what it means to them now and how they are a part of the story that has been written and is continuing to be written.”

[full circle]

Jessica Garcia felt a deep sense of nostalgia as she walked back into her high school for the first time in years — a fullcircle moment that she continues to relive each school day as she reports to her practicum site.

“I can’t believe where I am now,” says Garcia, a 2016 San Marcos High School graduate, currently earning a Master of Arts degree in school counseling at USD’s School of Leadership

and Education Sciences. She’s also completing a yearlong internship under the tutelage of her former high school counselor, Ruben Escobar. Now, he’s teaching Garcia what it takes to be a successful, caring and empathetic school counselor.

“It was an honor that one of my own students felt we had a connection that was above and beyond — that it left a positive impact on her to where she

felt that she wanted to pursue the profession,” says Escobar, a counselor at San Marcos High for eight years.

School counselors deal with every situation that comes through their doors. “The ultimate goal is to help students navigate the educational system and to have better opportunities upon graduation,” he says.

The two have a lot in common. Both identify as first-generation

Mexican-Americans who understand the difficulties that English learners face in school. Escobar came to San Marcos High while Garcia was a junior, and guided her through the college application process.

“He was there to support me and help me seek out different leadership opportunities,” Garcia says.

Garcia attended school in the San Marcos Unified School District from kindergarten through high school. Both her parents emigrated to Southern California from Oaxaca, Mexico. Agricultural farm workers, they only had education through middle school.

“Education is something they really instilled in me,” Garcia says.

Garcia considers herself a quiet student, which made navigating high school a challenge. San Marcos High is the biggest high school in the county, with an average graduating class of more than 800 students. She says the school had a reputation of providing leadership opportunities for students with diverse backgrounds. But it was meeting Escobar that put her on a course for postsecondary success.

“Jessica was one of the first students I met when I came to San Marcos,” Escobar says. “She stood out to me as a motivated leader who wanted to go places.”

Escobar recognized Garcia as an ideal candidate to apply for the Reality Changers College Apps Academy, a City of San Diego program intended to help firstgeneration students get into twoand four-year institutions, through college life preparation and maximizing financial aid options. The academy was founded by Chris Yanov ’03 (MA), a USD Alumni Honors recipient in 2010.

“It meant the world to me that someone was willing to get to know me and advocate for why I would be able to succeed in a college system,” Garcia says.

Following graduation, Garcia and Escobar remained in contact. As her educational track moved toward a focus in school counseling, Escobar brought up the opportunity for her to return to her alma mater. Garcia met with all eight counselors at San Marcos High.

“Everybody loved that she was our student and now an alumna,” Escobar says. “Right off the bat, she had a certain poise and charisma. Everyone wanted to have her back.”

For Garcia, it was a special feeling to return home.

“I have always wanted to give back here in North County in the same way that support was given to me.”

One student says, “This is a clothespin. It’s really great for pinning clothes but it’s also good for finger hats.” Another responds, “That’s right, Sam!” with the timbre of a game show host. “This is also a great hair accessory for when your hair gets in your face!”

A classroom of 22 students toss several clothespins back and forth, saying, “That’s right, Sam!” and then pitching brilliant and quirky ways that an everyday clothespin can be used. Sound a bit silly? Sure.

But this game of “That’s Right, Sam!” is a way to promote fluid thinking in a group brainstorming session and to show that any idea, no matter how strange it may sound, is worth sharing.

These ideation sessions were a part of the inaugural Student Sustainability Summit coordinated by USD’s Office of Sustainability and supported by the Changemaker Hub and Environmental Integration Lab. The event was not only the first ever of its kind at USD, it was also student led.

“Sustainability should be important to students because we’re supposed to be the Changemakers of the future generations to come,” says Mahlia Flores, a junior and a marketing and communications assistant for the Office of Sustainability.

The Student Sustainability Summit — which was made up of 70 students — listened to Director of Sustainability John Alejandro and Sustainability Coordinator Savannah Robledo

give a presentation on the university’s Climate Action Plan. Afterward, students were asked to choose between four topics — water and land, food, transportation or consumerism — and come up with ideas for projects that could become a part of the Climate Action Plan and help the campus continue to grow even more sustainable.

Flores was one of several students who was trained to facilitate the breakout sessions. She oversaw the topic of consumerism. “Every individual step we take toward making and creating sustainable solutions will not only implement change on our campus, but will also change the greater society as a whole,” she says.

Students broke up into teams of four to co-create ideas. They then were asked to step back and select the idea they felt should be sent on to the administration and considered as part of the Climate Action Plan.

“I hope students’ takeaway is that their time and effort don’t go unnoticed,” says Flores.

Students had the opportunity to apply to become a part of the Design Lab, a collaboration between the Environmental Integration Lab and the Changemaker Hub.

“We’re approaching this in a mindful, intentional and genuine way for students to gain agency around what they can do to be a part of change,” says Director of Social Change and Student Engagement of the Changemaker Hub Juan Carlos Rivas, PhD.

Those who attended all sessions qualified to receive a $1,000 stipend for their time and efforts. In total, the Design Lab selected 15 motivated students to join their team and continue cultivating ideas that could be included in the Climate Action Plan.

sandiego.edu/summit23

The University of San Diego’s Center for Inclusion and Diversity hosted its second annual Diversity and Inclusion Impact Awards Program and Luncheon in February 2023.

The program recognized 12 individuals who have “demonstrated sustained commitment to justice for communities historically marginalized for their race and ethnicity.” All university employees are eligible for the award.

“We are thrilled that the college and all schools are represented this year and we are proud to celebrate our colleagues’ sustained commitment to making USD a more diverse and inclusive community,” said Regina DixonReeves, PhD, vice provost for diversity, equity and inclusion and director at the Center for Inclusion and Diversity.

Sitting among family, friends and colleagues, the 12 recipients —

faculty members Jillian Tullis, PhD (College of Arts and Sciences);

Razel Milo, PhD (Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science);

Alison Sanchez, PhD (Knauss School of Business); Necla Tschirgi, PhD (Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies); Roy L. Brooks, JD (School of Law); Susan Lord, PhD (ShileyMarcos School of Engineering); and staff members Rebekka Jez, PhD (School of Leadership and Education Sciences); Hazel Claros,

MA (Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science); April Cash, MA (Knauss School of Business); Frances Laviscount, MS (Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies); Michael Chavez, JD (School of Law); and Elisa Lurkis, MA (pictured, Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering) — received their awards from USD President James T. Harris III, DEd, and Senior Vice President and Provost Gail F. Baker, PhD, along with Dixon-Reeves.

“There are so many people on this campus who are doing outstanding work on behalf of the University of San Diego and our diversity, equity and inclusion efforts,” Harris said during the event. “There is so much work to be done and there will always

be more that we can do. Each of these recipients is doing that work and, in the process, is inspiring the rest of us to follow their lead. They are undaunted. They are rolling up their sleeves. They are making changes — changes that move the needle. Changes that confront humanity’s most urgent challenges. Changes that our students, our prospective students and each one of us can see, and hear, and feel in our hearts and in our souls.”

“These are momentous times at USD as we forge our allegiance to underserved and underrepresented groups on our campus and in our community, to future generations of USD students and alumni, so every member of our community can thrive,” Provost Baker said to the audience, prior to recognizing the honorees.

The Impact Award was created in 2021 to honor and recognize the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) on campus. The award was established in response to an open letter written in 2020 by Black faculty members, and highlights the often underrecognized work by those who mentor members of the BIPOC community and contribute to cultural changes on campus and in the community.

The award is also part of The Horizon Project — a five-year plan led by President Harris in collaboration with partners across campus. The project is intended to help build a more inclusive campus community by setting specific strategic goals that touch on strengthening diversity, inclusion and social justice in a more diverse, multicultural and global world.

“Thanks to each of these recipients — and each of you here today,” said Harris. “Thank you for bringing The Horizon Project to life in your own ways through the work you do in the name of this university.”

s the new director of the Black Student Resource Commons (BSRC), Joshua “Jay” Rice is ready to hit the ground running. “This is very specific work,” he says. “For me, serving Black students ultimately makes me happy. And the institution benefits because of [increased] recruitment and retention of these students.”

Rice joined USD in December of 2022 after serving as assistant director for the Black Resource Center at the University of California, San Diego. Prior to that, he worked in student housing until he realized that his work gravitated toward Black student experiences.

“I realized that those were the things that sustained me — it moved from being just a job to there being passion behind it. I realized that I wanted to focus the work on a day-to-day basis to be about Black students.”

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the BSRC. It’s a space for advice and advocacy; a place for programs, events and services focused on the needs of USD’s Black community and a place to explore personal identity and shine a positive light on Black culture.

“We provide services that allow our students to develop academically and socially, and to explore their identity, which is extremely important, especially in understanding that we do exist at a predominately white institution,” Rice says. “The commons provides a physical space for students to study and to relax and take a break. It’s

an environment for intentional dialogue — one that really centers on Black experiences.”

Additionally, staff proactively works with other campus units to reach out to students who may be struggling. “We want to make sure we assist in setting students up for success, so we reach out to see how we can support those students and help them get back on sound footing.”

Other programs include the “Black And” series, which focuses on intersectionality and the weeklong Black Summer Immersion Program, aimed at helping Black students acclimate early to USD. “Sometimes our underrepresented student populations don’t have as much experience coming into an institution that allows for a sound and seamless transition. It’s about providing assistance.”

Additionally, the BSRC offers a peer mentor program for

first-year Black students. “There are a lot of conversations that are just better for students to have with their peers, because they’re able to provide a level of perspective that you might not get from the professional staff on campus. It adds a layer of validity to the advice.”

Rice is excited to grow the commons, and stresses that having dedicated resources for Black students at USD is paramount.

“Identity is such an important part of our lives. It doesn’t often come up in curriculum, but impacts the ways in which we learn and the ways we navigate the very spaces we are in,” he says. “Having a space that really centers Black student experiences also helps with inclusion, because it allows our students to see themselves reflected in the infrastructure of our institution, which is extremely important.”

The Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice’s Violence, Inequality and Power Lab (VIP Lab) will launch a new fellowship program intended to expand the breadth of work focusing on the relationships between power inequalities and violence.

“The fellowship program is an opportunity to create a space

for advancing the research, advancing the practice and fostering dialogue between practitioners and researchers with a very direct benefit to their own work and a broader benefit to the field overall,” says Rachel Locke, director of the VIP Lab.

The VIP Lab held a joint press conference with U.S. Rep. Sara Jacobs (CA-51) in the Ministry

Center on Feb. 15 to officially announce the creation of the lab. In late 2022, Jacobs secured $580,000 in federal funding for the Kroc School initiative. Jacobs advocated for the program and helped secure the funding through Congress’ 2023 Omnibus Appropriations Bill.

“Understanding the role inequality plays in perpetuating

the cycle of violence is key to building a more peaceful, just and equal society,” said Jacobs. “That’s why I was proud to secure federal funding to support the lab’s cutting-edge analysis, shape the broader field of study and invest in the next generation of research.”

USD President James T. Harris III, DEd, thanked Jacobs and spoke about the importance of the new fellowship.

The VIP Lab was established in January 2022 with an aim to “meet this moment by fostering collaborations that question the status quo, that use bridging language and that expand

access to nuanced knowledge and discussion.”

“Violence, is in large part, representative of power relationships that serve certain individuals or populations at the expense of others, often through systems of structural exclusion that create cycles of harm,” Locke explained. “Yet, while the centrality of power inequalities is increasingly known to drive violence, research on the topic is sparse. The VIP Lab was established to help reverse this trend, investing in knowledge, learning and creative collaborations to shift harmful systems of power and reinforce systems of peace and justice.”

The new fellowship will create more opportunities for thinkers and practitioners to advance the dialogue around violence prevention, Locke says.

The program will recruit research fellows with specific backgrounds that make them experts in their field such as veterans, those with law enforcement backgrounds and people who have been directly impacted by the criminal justice system. The inaugural class will consist of eight fellows from around the world who will research topics related to violence against women, violence in communities and political violence.

“I’m excited to welcome each of you to our campus as we partner with Congresswoman Sara Jacobs, who served as a scholar in residence at our Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, to share exciting news about expanding the work we’ll be doing through our Violence, Inequality and Power Lab,” Harris said.

“The work being done through the VIP Lab allows us to move past anecdotes and headlines to more fully and more accurately understand the scope and scale of urgent challenges and to become a part of the change this world so desperately needs.”

hilly evening temperatures and the threat of rain did little to dampen the energy and excitement of Toreros who attended a late February “Farewell to the Field” event at USD’s Valley Field.

Located adjacent to first- and second-year student housing in an area known as The Valley, the Valley Field is a popular campus outdoor space that’s been home to events ranging from intramural football games to employee picnics — and just about everything in between — since it was constructed more than three decades ago. The event marked the end of an era, as the space is being closed and redeveloped into the eagerly anticipated USD Wellness Center and Basketball Practice Center.

A collaboration between the Torero Program Board and Campus Recreation, the event had a carnival-like atmosphere where attendees were treated to an assortment of rides, food and music.

“Our main purpose was to throw a big party for the students in a place that has been a really important part of USD life for decades,” said Torero Program Board Vice-Chair Jasmine Hersh. “We were a bit nervous that it would just be Valley residents who would show up, but I was really happy to see juniors and seniors come back to celebrate and say goodbye. I know it was bittersweet for some people, but the overall vibe was really heartwarming and positive.”

Without a doubt, saying goodbye to the Valley Field — and its well-traveled neighbor, the Valley Stairs with its 70 grueling steps —

marks the end of an era at USD. And while they say that all good things must end … in this particular case, those good things are giving way to something great.

Slated for completion in August of 2024, the new Wellness Center will be USD’s state-ofthe-art nexus of health, wellness and community connection. Conveniently located, the threestory, 80,000-square-foot facility will sit near the main entrance of campus, at the crossroads between the academic area to the west and the residential and athletics areas to the east.

The center’s entrance and lobby will be located at street level, adjacent to the main campus entrance, parking structure, and Student Life Pavilion. This space will serve as the main thoroughfare to the center’s cardio and group fitness areas. The primary fitness area on the center’s third level will be the largest space on campus dedicated to exercise and physical well-being.

A wellness wing will be dedicated to supporting the mental and emotional resources needed for the challenges of college life and beyond. The fitness wing is the largest component of the Wellness Center. There, visitors will find extensive resources for a variety of physical exercises, activities and court-based sports, including the Basketball Practice Center.

Above all else, the Wellness Center is being built to provide students the opportunity to reach their fullest potential, and that, according to Associate Vice President for University Operations André Hutchinson, is reason enough to be excited about what’s to come.

“The facility was created with the idea that it can help optimize our students’ experiences; not just with their physical development, but also with their development as a whole person. That’s what we are committed to here at USD, and this facility will support that mission.”

[10th anniversary]

They are waiting to take a group photo with Donald’s wife, Darlene Marcos Shiley, the benefactress whose gift 10 years ago established the Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering at the University of San Diego. As she turns the corner into her self-proclaimed

“favorite space” inside the building, Shiley lights up at the sight of the young adults gathered in anticipation of her arrival.

“ ‘Shiley-Marcos!’ Oh my, those shirts are sensational,” she cries out joyfully to the students, wearing their

tops custom-made for this event — the 10th anniversary celebration of the school that carries her family’s name.

More students — and a few faculty members and staff — gather around the charismatic Shiley for an impromptu photoshoot.

Following the repetitive click of several cameras, she hangs around to learn more about the current students and to offer her appreciation for their dedication to pursuing engineering degrees at USD. She also references

the revolutionary workshop they occupy.

“This is my favorite space,” Shiley tells the group, as she looks up in reverence at the space that features an array of machines students use to turn their ideas into prototypes.

The space tells the story of Donald’s Garage, which not only pays homage to Donald Shiley, who was known for tinkering in his garage, but also celebrates the great things that can happen anywhere Changemaking engineers find inspiration.

“I wish Donald was here to see all of you,” Shiley says, “because he would have liked it.”

The hallways, atriums and workshops of the Belanich Engineering Center are alive with festive music, excited chatter and even the light buzzing of miniature drones making test flights in the airspace above nearby workbenches as onlookers attempt to capture photographs on their smartphones.

The celebration also includes 3D print demonstrations, Raspberry Pi robots, a 360-degree photo booth, raffles and a ceremonial cake cutting in the west lobby, where Shiley reflects aloud on the significance of the occasion.

“I can’t tell you how thrilling it is to see all of you here and to know there are students in the labs working,” she says. “I’m so proud of all of you. Thank you for continuing to let me help you — and I can guarantee that we are going to have some really good things coming up for the ShileyMarcos School of Engineering.”

Shiley also offered advice on the importance of leaning into change.

“Don’t be afraid of change,” she says, referring to the circuitous path Donald took

early in life — from leaving Oregon State University to enlist in the U.S. Navy during World War II, to finishing first in his class following the war at the University of Portland. “That’s why they call us ‘Changemakers.’ ”

“Donald Shiley was somebody who saw a problem and wanted to confront humanity’s issues around heart health and cardiovascular issues and he created something that has saved thousands of lives,” says President James T. Harris III, DEd. “When you combine that with the philanthropy and the vision of Darlene Shiley, the two married together, they are both Changemakers in their own way.”

USD launched its engineering department in the fall semester of 1987 and celebrated the graduation of its first cohort of electrical engineering students in 1991. During the next 22 years, the department grew and added Industrial and Systems Engineering and Mechanical Engineering degree programs.

In 2013, Marcos-Shiley

that founded the ShileyMarcos School of Engineering and Chell Roberts, PhD, was hired as the founding dean of the school.

“It has been so fun and so great to see what has happened,” Roberts says, reflecting on the anniversary. “We started 10 years ago with just a handful of faculty members. Now, we have more than 45 full-time faculty members. We had enrolled maybe 200 students at the time and now we have more than 800 undergraduate students and about 350 graduate students. We now have five undergraduate degrees and six graduate degrees.”

The 21st century is the world of engineering, Roberts says, referring to things like robots, artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality.

“There is this incredible world coming at us — we are diving into it and embracing it,” he says. “It’s the engineers and the computer scientists that create that world, certainly with others, but they are the brains behind the creation of our

should care about the school. We are creating the future.”

Earlier this year, the ShileyMarcos School of Engineering was ranked 15th on U.S. News & World Report ’s list of Best Undergraduate Engineering Programs where doctorate is not offered. The general consensus among those pivotal in its growth is that the school will eventually attain the top spot.

“Our engineers are going out and changing the world — we’ve got everyone from astronauts to individuals serving in the Peace Corps,” Harris says. “We have Toreros all over the world who are Changemakers and we are so proud of every one of them.”

“We have come so far in such a short period of time because everyone is really working together,” says Shiley. “It would make my husband wildly happy to know that there are so many different kinds of engineers here and I think he would look around and say ‘this is a group that was able to do amazing things in 10 years and I can hardly wait to see

[indomitable]

by Mike Sauer

Back when she was just 6 years old, Solymar Colling’s father, Randal, sat his youngest daughter down for a chat that would, eventually, define her future.

The conversation centered around sports; specifically, which sport Colling liked playing the most.

“I loved tennis, and I loved it because my sisters were already playing at that time,” Colling recalls. “I knew I wanted to play with them, and to beat them. My dad told me I needed to pick one sport to focus on, so it was an easy decision for me.”

That decision has paid bigtime dividends since, as Colling’s

athleticism, fiery competitive nature and storied work ethic have served as the foundation for a decorated amateur tennis career. Now a redshirt senior at the University of San Diego, her on-court accomplishments while a member of the Torero women’s tennis team are as impressive

as they are numerous. One in particular that jumps off the page is her being only the sixth player in program history to be named as an All-American in singles — and as a first-year, no less.

Yet, when that amazing achievement is brought up, Colling shrugs her shoulders and smiles, opting instead to talk about the success the program as a whole has enjoyed over the last few years. “Honestly, the memory that really sticks out to me about my career at USD was this year, when we qualified for the ITA Indoor Championships,”

she says. “We hadn’t done that since I’d been here, and that field has the best programs in women’s tennis. I think we all were really excited about that.”

While Colling is buoyed by team success, she also knows — and loves — the fact that tennis is a predominately individual sport. There’s no one to blame for your errant forehand. Or double fault into the net. The successes and failures fall squarely on your shoulders. “I’m a really aggressive player by nature. I like to try and end points quickly and go for big shots. And I feel freer to take those chances when I’m playing singles, because I know it’s all on me.”

Becoming a successful tennis player requires a robust interpersonal toolkit. Perhaps chief among those skills is the ability to — as the saying goes — embrace the suck. The hours upon hours of on-court work refining both your strokes and serve; the early-morning workouts; the long car rides from tournament to tournament. The ability to put the time in to improve often separates good from great, something Colling knows all too well.

“Honestly, I love practicing. I love the work,” she says, with a grin, “I might love it too much.”

Her dedication to improving her game has not inhibited her ability to excel in the classroom.

Colling is a three-time recipient of the Intercollegiate Tennis Association’s Scholar-Athlete Award and plans to pursue a career in real estate if she’s unable to pursue her primary goal of playing professional women’s tennis.

“Both of my parents are in commercial real estate, and I took an appraisal class that was life-changing,” she says. “I’m also studying to get my real estate license in addition to continuing to play tennis for USD, and training to play at the professional level after I’m finished at this level. It’s a lot … but I love it!”

CREDENTIALS: Kingsley has amassed an impressive set of laurels since transferring to USD in 2019. Perhaps most significant among them was his win at the Mark Simpson Colorado Invitational, where he stopped a stellar field from some of the nation’s best golf programs. “Having to wait to see if I won or would be in a playoff … that was probably harder than the golf.” PUTTING WITH POPS: When it came to developing a love for the game of golf, Kingsley didn’t have to look far for inspiration. Dad David Kingsley gave Harrison his first club to swing at the tender age of 2, and the younger Kingsley was “all-in from day one. I remember waking up early in the mornings when I was young, jumping on his bed and begging him to take me to the practice range.” GRIN AND BEAR IT: Kinglsey’s hometown of Murrieta, California, has been a wellspring of golf talent for several decades. It’s also home to one of the most challenging courses in a state replete with them; Bear Creek Golf Club. “I started playing Bear Creek when I was in high school, and I remember thinking how hard it was after the first time I played it; like, I was really frustrated,” Kingsley recalls. “But learning how to play such a tough course helped me learn to stay focused and patient, which is critical if you want to play golf at the highest levels.” LIVING THE DREAM: And speaking of highest levels, Kingsley is hoping to continue pursuing his dream of playing professional golf after he graduates this spring. He got a small taste of what PGA tour life might be like when he qualified for the Farmers Insurance Open at Torrey Pines last February. “Qualifying for the tour event at Torrey Pines was awesome, and I learned so much from the tour players while I was there.” — Mike Sauer

Four members of the University of San Diego’s leadership team were recognized for their work and for shaping the vision of USD’s future. They were part of the San Diego Business Journal’s 2023 list of the region’s “Top 50 Black Leaders of Influence.”

Among those honored were: Senior Vice President and Provost Gail F. Baker, PhD; Vice President of Student Affairs Charlotte Johnson, JD; Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Regina Dixon-Reeves, PhD; and School of Leadership and Education Sciences Dean Kimberly White-Smith, EdD, who called it “an immense honor.”

“This recognition not only celebrates individual achievement, but also the collective effort of our community toward equity and excellence. I want to thank the USD community, especially the faculty, staff and students of the School of Leadership and Education Sciences, for inspiring me with their focus on social justice and compassionate service,” said White-Smith who, since arriving at USD, has championed the Black InGenius Initiative (BiGI). The program explores thoughtful and innovative teaching techniques and provides a path to college for marginalized students.

Dixon-Reeves said she was humbled by the honor, and said as a first-generation student herself, and lifelong educator, she’s working to make USD a welcoming and inclusive place for students from all walks of life.

“As a community, we are committed to seeing and hearing people as they want to be seen and heard,” Dixon-Reeves said. “Using conflict resolution techniques to engage in difficult conversations while maintaining open lines of communication

and empowering every member of our community to safely and effectively intervene when they see something that contradicts our community values.”

Johnson has a long record of blazing a path forward for others. She is particularly proud to be in a position to do that in the realm of education.

“It is such a gift to serve as a person of influence in the higher education space given what educational opportunities have meant to Black people and other marginalized communities,” Johnson said.

“I am both proud and honored to receive this recognition for work that I care about so deeply, and to be included among a group of leaders who are advancing our communities through innovation, open hearts and the willingness to lift as we climb.”

“I am profoundly grateful for the transformative work of all the leaders who courageously devote their lives to open the doors of opportunity for others,” Baker added.

President James T. Harris III, DEd, says that each of the administrators who were recognized have played a key role in expanding the scope of the university’s mission, ensuring that USD remains at the forefront of Catholic higher education.

“These women are true leaders,” he said. “They are holding true to USD’s commitment to academic excellence in an environment that is open, expansive and welcoming — and have called others to be the same. In countless ways, they’ve inspired not only our students, faculty and Torero family, but the San Diego community at large. I’m deeply honored to count each of these four trailblazing women among my most trusted colleagues.”

— By Steven CovellaI grew up in Chicago, Illinois, and went to Catholic school and had an opportunity to take leadership roles in high school, being very interested in journalism, living through some real tumultuous times in Chicago and being really proud of our city’s heritage and history. All those things helped prepare me for the role I’m now in.

The University of San Diego attracted me to this role and I’m not sure I had previously spent any time in California. An opportunity to serve as provost of this university at this time in its history was very compelling. Even though I had lived in Florida for 11 years, you are always taken aback that you can be in March and the trees are green and the weather is nice. I was also impressed with USD’s commitment to its students, and the idea that through advancing academic excellence, we are helping to prepare innovative leaders dedicated to ethical conduct and compassionate service. When I hit campus, to see that it was not only a beautiful campus, but it also seemed like a calm campus, was nice. Then I met the students and it seemed like the place I needed to be at that point.

My late sister, Linda, was the smartest person I have ever known and a very spiritual and centered individual who took her Catholicism seriously. I wanted to do everything she did. My other sister, Jackie, teaches me how to be resilient. She never gives up. But the best advice I have ever received came from my father. I’m a firstgeneration college graduate and he would tell me — this is old Boy Scout talk — “leave it better than you found it.” I keep coming back to that any time I have an opportunity … is it better in some way that I can tell?

I see these young adults always trying to get to their destination. When I give them advice, I tell them to enjoy the journey. What experiences do you have along the way? There is a process where you are meeting people, you are succeeding, you are failing, you are turning corners. All of that is important, rewarding and joyful. When you are young, you just want to get to the next thing. I would encourage our students to enjoy the journey.

The provost is responsible for all teaching and learning on campus — it’s the academic leadership role. So if it’s in the classroom and it involves teaching and learning, that is what the provost does. Anything that moves the campus forward is what the provost is responsible for. Student success is the most critical part and that is not just measured in graduation rates. Student success is trying to get them to enjoy the journey, connect with one another, connect with faculty members, connect with critical thinking, connect with lifetime learning. For us, success means that our students are making it through and they are experiencing great teachers, great learning, great classrooms and internships, and that we are educating the whole person. I think we do that better than anybody.

We want to make sure our faculty members of color here feel supported and we have diversity programs in place to help with that. What we are trying to do is build cohorts with faculty so that faculty of a specific discipline may be able to find another faculty member in a different discipline where they can connect and learn about each other and that’s across all lines. We try to connect faculty members, work with them and support them. What students get from that

is a feeling that this is their community. We are trying to pay attention to every individual who comes here. We are trying to hear their concerns and be responsive and we are trying to increase the numbers so there can be an opportunity to build community.

My faith supports me. We have had some tough times the past couple of years with COVID and the George Floyd murder. If I didn’t have faith that there is a bigger power, that there is a place we are trying to go, that there is worth in humanity, it would be impossible to get up every day and face the challenges, as we say, “humanity’s urgent challenges,” because you wouldn’t believe you can get it done. Faith has been there with me every step of the way. I believe that God respects all human beings, that we have to respect one another and that there are better days to come.

I tell students that all the experiences they have — good, bad or otherwise — are preparing them for a future they do not know. While it seems like this is a dark time, and it is, I've also lived through other dark times and the students are the people who help lead us out and lead us into wherever it is we are going. Every experience you have you must absorb it, learn from it and you try to use it to improve the next experience. Don’t get marred if you can’t, think about where you are today and how you can use this to make tomorrow better.

The students give me hope. I see them every day and they are laughing and interacting and then they ask really tough questions and they care about the environment and humanity and diversity and respect and I think, “OK, if we can just get them ready, they’ll lead us out.”

— As told to Matthew Piechalak

Regina Dixon-Reeves, PhD Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Director, Center for Inclusion and Diversity

Regina Dixon-Reeves, PhD Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Director, Center for Inclusion and Diversity

San Diego is really different from Chicago. I absolutely love Southern California. It’s so funny, because I had never noticed how gray it was in Chicago until I got here. I remember how blue the sky seemed the first time I was on campus. I never considered myself a person with seasonal affect disorder, but clearly I suffered from it because it is so bright here that it literally makes me happy.

As a first-generation college student, my mom was incredibly supportive. She always encouraged me to ask questions, to seek out help and to keep asking if I didn’t get the answers I needed. Her best advice was for me to always be willing to talk to people, to put myself out there and not only ask for help, but also ask for resources and then follow through on those resources. That was the best advice I could have received and is the same advice I give to young people now.

Marquette University, where I earned my undergraduate degree, is a great Catholic, Jesuit university. There was a lot I didn’t necessarily take advantage of because I didn’t know to. That has fueled my passion for making sure young people know how they can get through school and fully engage in all its resources. I myself didn’t do an internship, didn’t study abroad, didn’t take advantage of career placement and career services the way I should have. Whenever I talk with young people, I encourage them to do those things because they’re important.

At USD, there’s an incredible commitment by both the president and the provost to make diversity and inclusion paramount in their list of priorities for the university. This community is passionate about diversity,

equity and inclusion and is really engaging in individual and institutional change. Since I’ve been here, what’s really struck me is that I haven’t received much pushback from anybody.

I see my role as helping us to develop a common framework, a common language and a common vision for how we get where we want to be. I am trying to approach the work systematically and through best practices. We know from research that diversity equals excellence and that diversity equals a better environment for everyone. In order to have a more diverse community, we need to attract a more diverse applicant pool and give them an equal chance of being hired. But once we get them here, we also have to give them opportunities to grow, thrive and be successful.

One of the things I’m most proud of is that over the past four years we’ve seen increasing enrollment of students of color across the board. And particularly in the last three years — especially since we stopped using ACT and standardized scores to admit undergrads — we’ve found that those students are competitive and that they are doing as well as any of the previous cohorts before them.

This year’s strong and diverse applicant pool will hopefully counter people’s fears that the more students of color we admit, the less prestigious we will be. What we’re showing is that the more diverse we are, the better we are. These students are on track to continue to be retained and to graduate. That’s important because it shows that diversity really is our strength. It’s our academic strength and it’s our intellectual strength. Diversity of opinions, thoughts and experiences makes for a rigorous intellectual environment.

You can’t have community if people don’t know each other. It’s incredibly important to have small intimate gatherings as well as large communal spaces where people have an opportunity to meet and interact with people that they might not normally interact with. We work on programs that really allow us to share the various sides of who we are. It can’t just be science and math at the exclusion of the humanities and the social sciences. We are an interdisciplinary community.

Even in contentious times we can find hope every time we look into one of the young people’s eyes that we meet here on campus. We find hope in the fact that we have students and faculty and staff who say, “I’ve lived through this pandemic and I’m still here. I was born for such a time as this!” That should give us hope. Every time we look at the accomplishments of our students and alumni, that should give us hope because we have contributed to someone who is going to be a Changemaker. I find hope when I look at our incredibly committed and impressive faculty and the work that they are doing and the issues they are tackling.

Jesus himself was a social justice advocate. He spoke for people who were disenfranchised. It is His message of love that we extend to the people who come into our community. That gives me hope, because I feel that love from other people as well. So, I hope that we know that we are preparing people to go and engage in those ways. For myself, I absolutely love being at USD. I am so grateful that you all took a chance on me. There are other people who could have done this job. I am grateful to be in community with you, doing this work that I love.

— As told to Julene Snyder

My parents grew up during segregation in the South and I was born in the midst of the Civil Rights movement. These two things had a profound influence on my own life journey. Having parents who were born and raised during the Jim Crow era and who started their family at the height of the Civil Rights Movement are forever a part of my DNA.

Growing up, I learned early on that everyone deserves respect. In the Catholic faith, there's an emphasis on self-reflection and being the best people we can be. Those are themes that have run throughout my life and they are principles I try to bring to my work. Treating people the way you want to be treated is a lesson that has been ingrained in me since I can remember.

My parents placed a huge emphasis on education. My grandmothers were domestics, my grandfathers were laborers, one was a stone mason and the other had little formal education. Now, in the three generations since my grandparents, we have lawyers, educators, physicians, business owners, accountants, engineers, you name it. I’ve seen how education transforms not only individuals, but also families and communities.

The USD opening was presented to be a potential good fit. During my first interview, I thought there could be value alignment. Additionally, despite the fact that the interview was over Zoom, there was a certain warmth generated. I was invited to campus for the second-round interview and had an opportunity to meet people and get a feel for the community. I left that day believing it could be a really wonderful fit. I believed this position could provide

me the opportunity to be my full and authentic self, to incorporate all parts of me in the service of educating our students.

Thanks to my parents and grandparents, I had a deep spiritual upbringing, a strong belief in the power of God — it’s a strength we can fall back on and use to propel ourselves forward and help others. Part of what faith and religion have meant for me is never giving up, having faith in yourself and having faith that things will work out according to God’s plan.

Being a lawyer taught me to be strategic, to think from multiple perspectives, to be an effective communicator and to tell a story in ways that will influence, sway or compel people to take some action. I loved the intellectual stimulation. The part I didn’t get so much in my particular law practice was being radically compassionate. I had to shore that up, especially moving to student affairs and working with people who had dedicated their careers to supporting and helping students develop.

I had never thought about completely leaving the practice of law. Then I got a call from Saul Green. We were on a University of Michigan Law School committee together, and he told me the law school was looking for a new position called director of academic services. The law school dean asked people to put out feelers and I’m told my name kept coming up. When Saul called me, I said, “No, I’m not applying. Why would I ever go back to the law school as an administrator?” He said, “You may not want to do it now, but your name is already out there. Dust off your resume, write a cover letter and keep your name circulating because you may want to take that path later.”

I am blessed to have a team of people who are dedicated to student growth and development. Through the Thriving Student Model, we’re asking, systematically and strategically, how we not only help students succeed, but how we help them thrive. And what does thriving really mean in the 21st century at a contemporary Catholic institution like USD? We’ve divided the model into several categories — academic success, inclusive community, belonging, holistic wellness, experiential learning and, the thing I love the most, joy. We want to help students experience meaning and thriving in all categories. We don’t just ask how to help students, but how to help all students. In that sense, the model is anchored in inclusive excellence.

Nationally, the mental health of college students is a significant concern. At USD, we are increasing access to mental health services and support. One way we’re doing that is by expanding the diversity of counselors in the counseling center. We have Black, Latino and bilingual counselors. One counselor is both a USD alumnus and a veteran. We want students of all backgrounds to feel comfortable coming to the counseling center. That’s one example of how we think about inclusivity and how we serve a diverse population of students.

Our students make me feel hopeful about the future. I love students at USD. They’re smart, they’re dedicated, they work hard and they care about each other and are strengthening their compassion. The culture of care we talk about at USD is real — and part of the reason it exists is because our students are heavily invested in community and in each other.

— As told to Kelsey Grey ’15 (BA)

Kimberly White-Smith, EdD Dean, School of Leadership and Education Sciences

Kimberly White-Smith, EdD Dean, School of Leadership and Education Sciences

I grew up in a nontraditional way. I was raised by Cleopatra and DC White, who were born in 1919 and 1917 and encountered America when segregation was at its height. Neither were college educated, but they had a strong belief in education. When coming up on retirement, they trained as foster parents and opened their home to children like me. Living with them was an amazing experience — I had an opportunity to see what it looked like to advocate for academic justice.

In high school, I began to see the challenges and obstacles faced by students who come from nontraditional households. I had an advisor who told me that people like me didn’t go to college — and she didn’t support me in trying. I lived in South Central Los Angeles and had a friend at an all-girls Catholic high school in Inglewood who was trained as a peer counselor and helped me fill out college applications. I was accepted into a few UCs, including Berkeley. I took those letters of acceptance back to my high school counselor and I said, “I understand if you don’t want to help me, but can you tell me this? Which of these places is the farthest away from here?” She said Berkeley was the farthest.

I didn’t know anything about Berkeley, but I knew, in my heart, that’s where my parents saw me going. They passed away, but I kept them with me. My sister — Cleo and DC’s biological daughter — went with me. I packed a suitcase, got on a plane and we stayed in a dingy motel until we got the dorm situation sorted out. None of it was easy. That’s why it’s always inspiring to meet students who have diverse, nontraditional experiences as they come into higher education, because it says a lot about their journey, strength and what they overcame on their way to where they are today.

I had a tough time as an undergrad, but that’s when I learned the importance of finding mentors and finding curricula that sings to you. I was a psychology major and an African American Studies minor and had the opportunity to learn about our history and our contributions to the world. That’s when I began to understand the trajectory of my parents, what they went through and why they felt it was so important to give back to their community.

At Berkeley, I took a course taught by Dr. Bil Banks about the historical perspective of Black education in America. After grading one of our exams, Professor Banks passed them back to students, but I didn’t get mine. After class, I told him I didn’t get my exam. “That’s because I wanted to talk with you,” he said. “You got 100%. Have you ever thought about going into education?” He mentored me and encouraged me to apply to grad school. I got my master’s from Teachers College at Columbia University and went on to teach in elementary schools and continuation high schools. Then I decided to work for a nonprofit, recruiting people of color and training them to be exceptional teachers. That’s where I met Dr. Judy Johnson, who encouraged me to get my doctorate.

We already know the inequities that exist in the education system — I was tired of talking about the problems. So, I decided to research communities where schools were getting it right. I talked to teachers, families and principals. I realized the success of these schools was a function of good leaders. So, I studied leaders who produced high student achievement in schools that served minoritized communities. I was pregnant while collecting data. Once my daughter, Chloe, was born, she’d sit on my lap and I’d bounce her on my knee while typing my dissertation. Everything I was doing was about

my family. They were my inspiration. It made sense to me to bring her along so she could see mommy working. It made sense to read aloud to her while I was writing and to model to her what it was like to work in these spaces. Chloe was salutatorian of her class. She identifies as someone who has dyslexia, but she’s paving a way for herself in the education space and thinking about what her next steps will be.

In the School of Leadership and Education Sciences (SOLES), we offer mental health and leadership programs. We have counseling and marriage and family therapy programs. We have a compendium of centers and institutes. We have a Catholic education program. We’re training people to work in student affairs, in nonprofit leadership and management and in pre-K to 12 schools. My vision is to develop an ecosystem where these programs, centers and institutes can work together to prepare SOLES graduates to better serve all students.

I find hope in students who are earning their PhD in social justice, students who are in our leadership studies program or in our marriage and family therapy program, students who are earning their licenses and their credentials to become teachers in our schools. I find hope in people who are making affirmative choices to be part of what we’re doing in SOLES and trusting us to give them the tools they need to succeed in community environments that might present obstacles. I find hope in our students who are making midcareer changes to become education advocates. Cleo and DC taught me that education has the potential to build pathways. The work for us, within SOLES, is to reshape education to allow for honest conversation, to create concrete change for people who are oppressed, to provide tools for social mobility and to form a more humane society. — As told to Krystn Shrieve

Anita Duong grew up unaccompanied. She was unattended, unprotected. Abandoned. Alone. That was then. And this is now. Now, Duong ’23 (MA) is a scholarly success. She earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology from San Diego State University and in 2021 graduated cum laude. Under her gown, she wore a black dress from Forever 21. Her commencement stole was purple and white, colors used to symbolize foster youth.

Celebrating the renaissance of some of USD’s most resilient students

Story by Krystn Shrieve

This month, she walked across the stage again, this time at the Jenny Craig Pavilion, with a Master of Arts in higher education from USD’s School of Leadership and Education Sciences (SOLES).

Kimberly White-Smith, EdD, dean of SOLES, is well aware of the obstacles students like Duong face, especially having been raised in the foster care system herself. [See her story on page 25.]

“When I meet students who’ve made it through the gauntlet, I’m excited and proud because I know what they’ve been through to get here,” she says. “I’m also aware it doesn’t have to be that hard. A program like Torero Renaissance Scholars (TRS) is one pillar that fills in the gaps and help us navigate educational systems.”

Another pillar is SOLES, which prepares teachers to address the needs of students who come from nontraditional households, learn differently or are neurocomplex.

“That’s why Anita’s presence is essential, why it’s vital that she’s represented in the higher education space and why it’s important that she’s earning a master’s degree from SOLES, which will help her better serve this community,” WhiteSmith says. “Just as I may be an inspiration to her, she too is serving as an inspiration to those who come behind her.”

After turning her tassel, Duong plans to earn her doctorate in higher education.

“My goal is not just to become an educator and a scholar but an

advocate for foster youth,” says Duong, who is among the less than 1% of the nation’s foster youth who’ve earned a master’s degree and now hopes to join White-Smith as one of the even fewer in the ranks to complete her doctorate. “I’ll champion other students, like me, who work so hard to overcome the disadvantages they face. I’ll represent those who are underrepresented. I want to give these students their chance, their opportunity to have their voices heard, to have their dreams fulfilled. I want them to have their own renaissance.”

During her time at USD, Duong was involved in Torero Renaissance Scholars, a program that provides support and resources to USD students from across the United States who identify as former foster youth, who are emancipated or unaccompanied minors, who were in legal guardianships, or who are homeless or are at risk for becoming homeless. [See the sidebar on page 31.]

The program was established at USD in 2010 by former Assistant Vice President for Student Affairs Cynthia Avery, EdD. Avery spent time as a courtappointed special advocate and understood the struggles foster students often face in school.

“After arriving at USD, I asked what support systems were in place for former foster students and students who were homeless or on the verge of

becoming homeless,” she recalls. “I was told USD didn’t have students in those circumstances.”

But Avery knew of students on campus who were homeless, hungry and struggling to meet basic needs — all while attending classes and juggling life as a student.

Within a year or so, the FAFSA form — officially known as the Free Application for Federal Student Aid — added questions that allowed students to note whether they were foster students, unaccompanied minors, emancipated minors or homeless.

“That changed everything,” Avery says. “Now, the Office of Financial Aid can identify students whom we could invite to join the TRS program.”

Another major turning point was when TRS gained the attention of two anonymous donors, who generously gave a significant contribution to support the work of the program. They said their goal was to serve as catalysts for others and to provide students with opportunities they might not have otherwise had.

The TRS program started with three students and, this year, serves 15.

Duong is proud to be one of those scholars. Her own story was part of a generational trauma that began years prior.

Her grandmother grew up in Cambodia and survived genocide at the hands of the Communist regime known as

the Khmer Rouge, which came to power in the spring of 1975 after overthrowing the president of Cambodia. Over the next four years, the Khmer Rouge systematically killed more than 2 million people, including anyone thought to be an intellectual — doctors, lawyers, professors, teachers, those who spoke a foreign language, those who were leaders in the community and even those who looked scholarly simply because they wore glasses.

After living through that, Duong’s grandmother came to the United States when Duong’s mother was 5 years old. Life here had its own difficulties and her grandmother suffered abuse at the hands of her husband. Eventually, her grandmother found the courage to leave her husband, but subsequently struggled with depression and alcoholism.

Duong’s mother had no choice but to step up to care for her younger brother. That meant years later, having done her duty, the last thing she wanted to do when Duong was born was to be a mother.

She wanted to dress in fancy clothes. She wanted to drink. She wanted to party. She wanted to enjoy the freedoms she didn't have while growing up.

The last thing she wanted was to take care of a baby or to be tied down.

Duong has hazy memories of her mother and grandmother drinking together, with music blaring in the background. The

more they drank, the louder they'd crank the music. Before long, the women would yell at each other until Duong’s mother would inevitably storm out of the house, vowing never to return.

“Chaos would ensue,” Duong says. “They’d yell, argue and throw things. I’d hide in my grandma’s room and cry until it was over.”

Eventually, Duong’s mother fled to New York for a decade with her new husband. After that, Duong’s mother existed primarily in photographs.

Duong grew up with a fantasy she played over and over in her mind, of her mother picking her up from school the way other moms picked up friends and classmates.

In Duong’s mind, her mother drove a red Lexus. She wore a beautiful skirt and blouse with blue flowers and long, flared sleeves that billowed as she walked. Her hair was curled and her makeup was simple — light mascara and blush in a soft shade of pink.

“I imagined her walking to my lunch table and surprising me,” Duong recalls, with the trace of a smile on her lips. “She’d hold my left hand and I’d wave goodbye to my friends as we drove off.”

Duong’s father, originally from Vietnam, was in prison for shooting a man and was still serving his sentence when Duong was born. She was 8 years old when he was released. Duong resented him for leaving her alone with her mother, who abused her. But he was abusive too — slapping her across the face, slamming her head into a window, pushing her down and kicking her in the stomach.

He constantly shut her out of his room, where she couldn’t help but notice white powder on his desk. He even took her along on drug runs, leaving her in the car while he was buying or selling. One day — in a state of

paranoia fueled by cocaine — he nearly killed an elderly man in nearby Linda Vista, whom he was convinced was following him.

Soon, he was back in prison.

Duong spent her childhood bouncing around from one relative to another, until her welcome expired. Some were abusive. Some were merely inattentive. She carried her belongings in a blue, plastic laundry basket and had only one item she truly treasured — a toddler-sized yellow blanket with a brown bear holding three balloons — one red, one green and one blue. Bought

at a flea market, she carried it everywhere she went.

Eventually, Duong moved in full time with her grandmother.

“I call her mommy,” Duong says lovingly, of her grandmother. “She’s the true definition of resiliency. She survived the genocide. She came to a foreign place where she didn’t know the language. Her husband abused her and cheated on her and, eventually, she decided she was better off navigating alone.”

Grandmother and granddaughter lived together in a humble, two-bedroom home in City Heights. One

room belonged to Duong’s uncle. She and her grandmother shared the other room.

“My grandmother had a lot of regret with her own kids,” Duong says. “Now, she’s working hard to be a proper mother, through me, but I feel bad that she had the responsibility of raising me.”

Watching television shows and movies, Duong knew other families were different, but it wasn’t until she was filling out paperwork with a financial aid counselor during her senior year in high school — and the counselor checked the box indicating Duong was an

unaccompanied minor — that she truly understood just how different her life was.

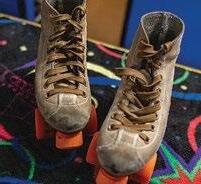

Duong says, as a young girl, her uncle bought her a pink-and-purple Huffy bicycle, complete with decals of her favorite Disney princesses and colorful metallic tassels that would flutter from the handlebars as she rode against the wind. Her uncle took her and her cousin camping and to the roller rink.

“I’m so grateful to my uncle for helping to normalize my life and for giving me great memories,” Duong says, while gliding on her purple roller blades. “To this day, I still love roller skating. I feel so safe, so relaxed, so free.”